MENAPOL Blog

Approaches to and Challenges in Implementing Competition Law and Policy in the Arab World

Economists have long stressed that great benefits flow to an economy from the introduction of well-defined legislation governing the rules of monopoly and competition. Modern competition laws have been around for over 130 years—and even thousands should one consider early embryonic versions. Conversely, the majority of the Arab countries have been latecomers in adopting such a significant piece of legislation, and when adopted, implementation has been lukewarm, and even weak.

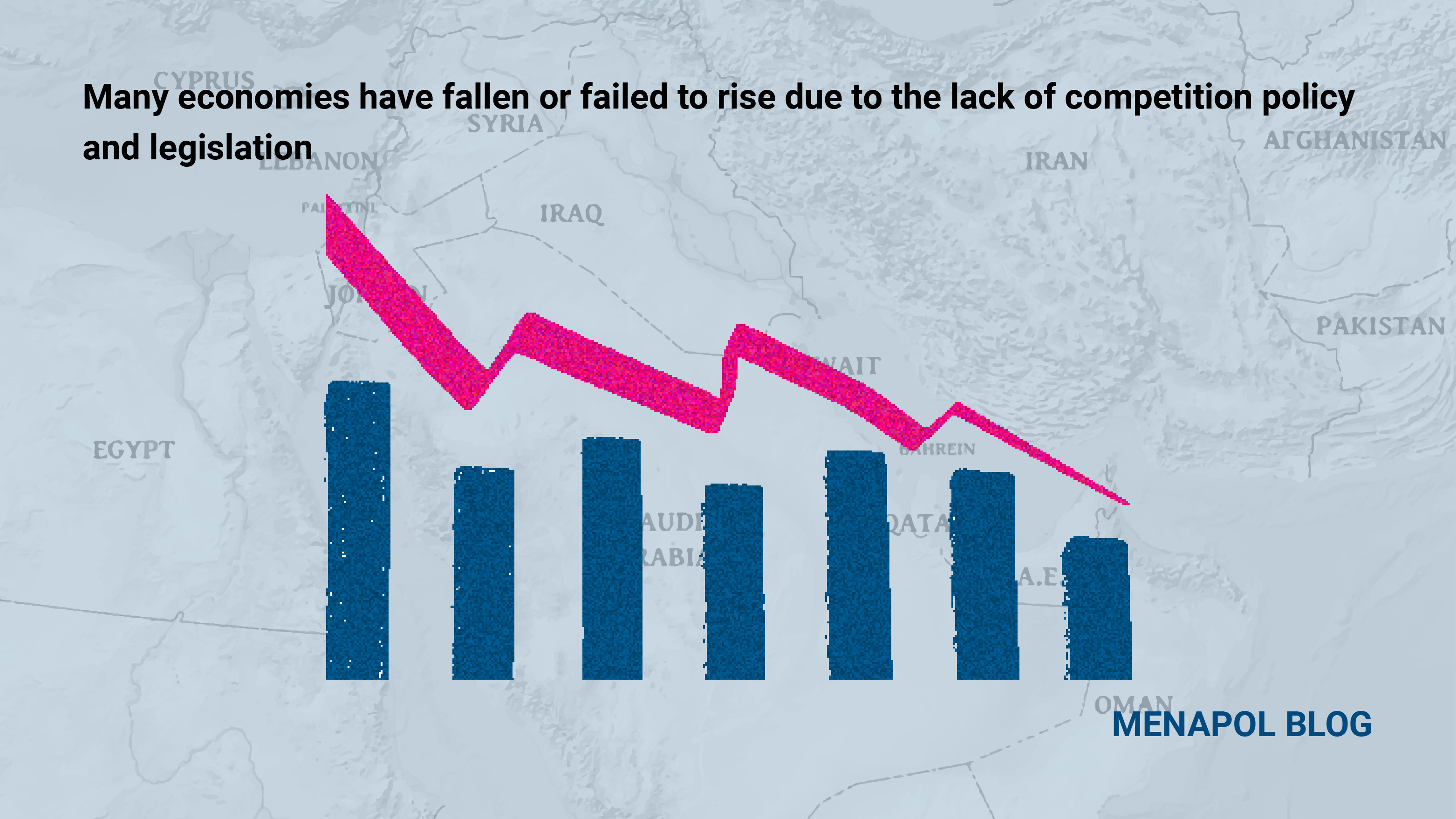

Many economies have fallen or failed to rise due to the lack of competition policy and legislation. Why? Because any type of market system requires that the market be efficient, not distorted, especially through the anti-competitive or abusive behavior of firms. The necessity of having a competition law and policy in place in a country is, thus, apparent. Furthermore, in the current era of high inflation rates, it does not require a great deal of imagination to picture how the disadvantaged and the poor would be affected much more adversely than the rich by monopolistic practices. Hence, any country that desires to develop its economy must introduce and properly implement a form of anti trust legislation.

Origins of Competition Laws

Modern competition laws started in the US with the introduction of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was followed by the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, and the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950. However, one need not think that competition policy is a new advent. The Romans passed tough laws imposing heavy fines on anyone causing the scarcity of supplies or creating price distortions. All the old monotheistic religions have had something to say about hoarding and acts of monopoly. In the Middle East and North Africa, the roots of competition law and policy can be traced to the emergence of Islam in the seventh century, long before Adam Smith spoke about competition in the 18th century.

There are currently 125 countries that have competition laws, with the vast majority of them conducting active competition enforcement activities. Of the 22 Arab countries, only Tunisia had competition legislation by 1991—one century after the introduction of the Sherman Act.

The Arab countries that currently have competition laws are Tunisia (1991), Yemen (1999), Morocco (2001), Algeria (2003), Jordan (2004), Saudi Arabia (2004), Egypt (2005), Qatar (2006), Syria (2008), Sudan (2009), Iraq (2010), UAE (2012), Oman (2014), and Bahrain (2018). Note that the modalities of implementation, some of which will be addressed here, differ from one country to another.

Forms of Competition Law

There are several internationally agreed forms of competition law that embody to a great extent similar, well tried and tested components. According to the European Union and United States, the Anti Competition Restraint Law of Germany, and the UNCTAD model competition law, an antitrust law typically includes three broad elements: anti cartel or collusion mechanisms; restrictions against abuse of dominance or monopoly power; and regulations controlling mergers, acquisitions and amalgamations, which would concentrate market power in the hands of fewer companies. Such a law would entail penalties associated with infringements upon the law that vary from one country to the other and are usually levied in addition to existing penal codes, not in lieu thereof.

External Influence

Some of the Arab countries only introduced such legislation after having signed Association Agreements with the EU under the 1995 Barcelona Declaration, which stipulated that the signatory to the agreement should make their competition legislation compatible with that of the EU. Other Arab countries, which have not signed such agreements with the EU but were seeking membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO), have had their competition legislation scrutinized and were encouraged, as a precondition for accession, to become compliant with the standard rules of competition.

Making policy is much easier than implementing it

This cannot be truer than in the case of the implementation of competition policy in the Arab world where governments, to meet outward commitments have adopted some first-rate competition legislation, but drastically failed to implement it. In many cases, implementation was lack luster, and little has changed in terms of enhancing competition in markets to spur competitiveness as political pressures by the elite suppressed investigations and follow up.

In addition, many of the Arab countries conducted privatization processes, which entailed the transfer of public monopolies into private ones, without having competition laws to ensure a resultant efficiency through competition. Competition laws should have been introduced and implemented prior to such privatizations that included market liberalization and national infrastructures.

The staff of organizations within the bodies tasked with administering competition legislation is appointed by the executive bodies (governments), not governments which can make them submissive to political pressure and cronyism. In some countries, like Jordan, the legislation, when introduced, was supported by weak, non-independent implementation structures and mechanisms, or hurdled by lack of expertise and awareness. Also, the judiciary that is handling competition cases is often not trained in the technical aspects of competition in order to competently handle competition issues like “bundling”, “margin squeeze”, “the HHI market share measure”, and other terms that are well known to economists are not taught in law schools in the region.

Consequently

Monopolistic practices, which create inefficiencies and market distortions, continue to plague many of the Arab economies. Hence, concerted efforts by policy makers aimed at enhancing competition within the Arab economies, a main ingredient for achieving competitiveness, should be undertaken with a sense of urgency. Some Arab countries have already started to do so; let’s hope that all will ensure in the near future the proper implementation of state-of-the-art competition laws.

Dr. Yusuf Mansur is Chief Executive Officer of Envision Consulting Group (EnConsult). He is also CEO of Mafraq Center for Development, Economic Research, and Analysis (MACDERA), a non-profit organisation that focuses on addressing macroeconomic policies, development, poverty, job creation, and empowerment in Jordan's poorest regions. Dr Mansur is former Minister of State for Economic Affairs and he served as a Member of the Prime Minister's Economic Policy Advisory Committee.