Freedom on the Net

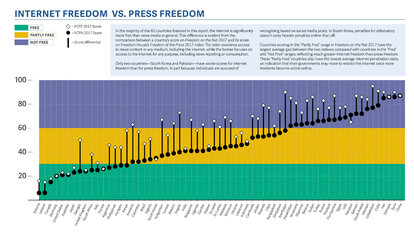

The non-governmental organization Freedom House based in the U.S. conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights. The Freedom on the Net Report 2017 informs about freedom in the digital age.

The report provides analysis of existing restrictions on speech online and it highlights the emerging threats. Freedom on the Net has also newly launched the Internet Freedom Election Monitor to estimate the risk of restrictions on internet freedom during upcoming elections.

Nowadays, people rely more and more on the internet. Therefore, it is important that rights as the freedom of speech, information, privacy, and association are also protected online. It is fundamental to enshrine these rights in international covenants to uphold liberal democratic values. Even in closed societies, technology can create a limited space for freedom online and bypass political and media restrictions.

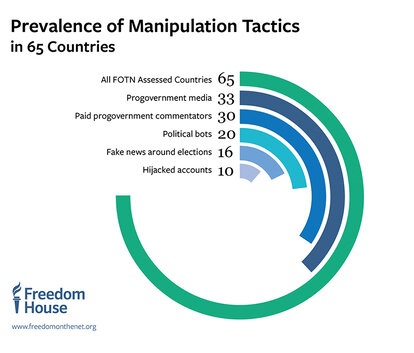

But technology can also be used by enforcers of government censorship and surveillance. Authoritarian regimes are more and more exploiting the internet for individual empowerment and are building new barriers in the online domain. Freedom on the Net measures internet freedom in order to identify threats to online freedoms and opportunities for positive change to encourage individual rights. It measures the ways that governments and non-state actors around the world restrict the individual rights online. The specialists analyzed three categories:

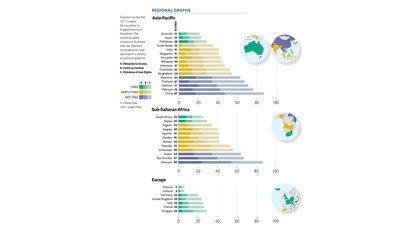

- Obstacles to Access: infrastructural and economic barriers to access, legal and ownership control over internet service providers, and independence of regulatory bodies;

- Limits on Content: legal regulations on content, technical filtering and blocking of websites, self-censorship, the diversity of online news media, and the use of digital tools for civic mobilization;

- Violations of User Rights: surveillance, privacy, and repercussions for online speech and activities, such as imprisonment, extralegal harassment, or cyber-attacks.

The report covers 65 countries. The countries are selected on the basis of the size of their internet population, their regional or global relevance, as well as the unique quality of their restrictions or protections on the internet.

Case study Myanmar

Internet and mobile access have increased dramatically since Norway’s Telenor Group and Qatar’s Ooredoo entered the telecommunications market alongside state-owned Myanmar Post Telecommunication (MPT) in 2013. Between June 2016 and May 2017, mobile phone dispersal jumped to 90 percent, although women remain significantly less likely to own their own devices as men.

On the other hand, internet freedom declined after the transfer of power to the National League for Democracy (NLD) party. The new government has been criticized for failing to check prosecutions involving online speech under the Telecommunication Law. At least 61 people were prosecuted for online speech and several were held for weeks without bail, some were sentenced to prison. Politicians, military, and ordinary internet users were sued based on criticism, satire, and commentary published online. Furthermore, violent attacks were reported against at least two journalists active online. One journalist was killed, possibly in relation to social media posts exposing illegal logging.

Obstacles to access

Internet access is improving in Myanmar, as increasing numbers of users go online via cell phones, which are becoming more affordable. Yet internet penetration still ranks among the world’s lowest. The infrastructure is inadequate and therefore, the speed and quality of service remains poor. Users in most provincial towns have much poorer quality connections than those in major cities. Poverty also continues to limit citizens’ internet usage. In addition, military conglomerates are still positioned to benefit from the system and manipulate the telecommunications market.

Limits on Content

The government lifted systematic state censorship of traditional and electronic media in 2012. Still, authorities make an effort to exclude certain topics from mainstream discourse in ways that lack transparency. During the coverage period, military and self-styled pro-democracy activists actively pressured online media users they perceived as critical. This pressure promotes a high level of self-censorship among the users. People are reporting rival Facebook users for violating the site’s community standards and are publishing manipulative political commentaries to harm their opponents. Moreover, even though digital content was not subject to censorship, sensitive political and social topics were underrepresented online. Self-censorship with regard to military and related issues is a common practice. Journalists are also becoming more cautious when reporting on the NLD government. Online content is subject to some manipulation, though the extent and impact are unclear.

Violations of User Rights

The current constitution does not guarantee internet freedom. Some laws explicitly penalize online activity and have been used to imprison internet users. The 2013 Telecommunications Law introduced a defamation provision which was used to jail dozens of internet users for political speech. The law includes broadly worded clauses that subject internet activity to criminal punishment. The NLD government has refused to repeal or initiate a significant remedy of the Telecommunication Law. Government officials, NLD parliamentarians and NLD party members brought charges against anyone they perceived to be opposing them online. At least 14 journalists have been charged under Clause 66 D.

Beyond, at least two incidents of violence against journalists were reported during this coverage period. Both worked for traditional media outlets, but may have been targeted in part because of information circulated on the internet. In addition, media and civil society websites are constantly subject to cyber-attacks and hacking, including at least one incident under the new government.

Sources: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2017; https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2017/myanmar