#FEMALEFORWARDINTERNATIONAL

A leader’s fight for freedom

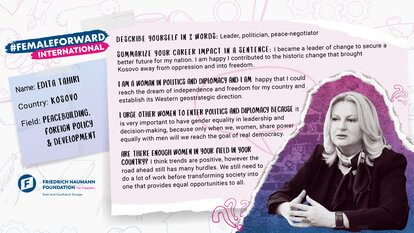

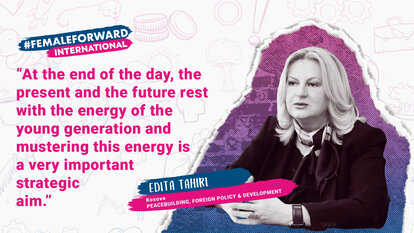

The story of Kosovo leader Edita Tahiri – from the struggle for independence to wartime peace negotiations and on to today.

Very few women in the world can start their life’s journey as one of an oppressed people in their country, grow to become the voice of their new-born nation to the world, help it earn its freedom, and then not only live to tell the tale, but also make a successful political career. Edita Tahiri from Kosovo is one such rare example, and she has many stories to tell.

These tales range from being a founder of a movement for independence from Serbian occupation, the Democratic League of Kosovo, to her relentless political and diplomatic work for the liberation and international recognition of Europe’s youngest country. But they all simmer down to one, which she describes as her most significant life achievement: “I am proud that we brought Kosovo freedom and independence and ensured that Albanians would never again suffer from genocide.”

A Kosovo patriot is born

Tahiri was born in 1956 into what she describes as a very patriotic Albanian family. Her father was a native Kosovar, her mother an Albanian, and they married in Kosovo during World War II when borders between these two countries hardly existed in practice. Her father longed for the reunification of Kosovo with Albania and was not only a patriot in principle but, as an underground politician, he suffered imprisonment and torture at the hands of the repressive post-war Yugoslav apparatus led by the Minister of the Interior, Aleksandar Ranković. “I saw oppression against Albanians through my father's eyes and the division of Albanians through my mother's eyes – that shaped my personality and my attachment to my nation’s destiny,” Tahiri says.

She was not a politician by nature or education – in fact, her first degree was in Telecommunications and though she dreamed of studying Psychology, (“I wanted to understand my father’s suffering”), she could not ignore the plight of her family and her people. Fate, however, would soon reward her prudent choice of education, pushing her in a direction she could not have dared imagine. After earning a bachelor’s degree in Pristina, she would move on to a Master’s in Essex, UK, becoming one of the first Kosovars to experience the West. This educational detour would shape her path soon after she joined the movement for Kosovo’s independence.

In the first days of the independence movement, Kosovo’s best and brightest nominated her to be the Minister of Foreign Affairs of this still non-existent country. There were two main reasons for that, she says: “I came from a credible, patriotic family that fought in defence of Albanian rights and I was already educated in the West, so I was not only English-speaking, but also exposed to Western culture and its system of education.”

“At the time, it was very important to have people who were patriots, well-educated, and not nostalgic for communist times. Our movement’s leadership were all nationalists, we were the elite of Kosovo,” she recalls. The fact that she was a woman was secondary at that time. “When the nation is in danger, there is no place for gender,” she laughs.

From the corridors of diplomacy to the White House

Then came the difficult part. In 1991, the international order was changing rapidly due to the end of the Cold War and of communism in the Soviet bloc. During the Cold War, Yugoslavia, dominated by Serbs, had pursued a “third way” between East, West, and the Global South; a policy which made it many friends in high places. It was no easy task to convince the world that Kosovo now deserved the same independence from Serbia as the other federal units of the former Yugoslavia and that its people had already spent a century fighting for their country’s freedom.

The difficulty was that the international community did not understand Kosovo’s situation while her country, in turn, lacked access to the international community. Edita Tahiri recalls: “A chief diplomat that is denied access to international institutions and important countries requires a lot of creativity to make progress. When I started as foreign minister, diplomats didn't like to meet with me because they didn't understand what was going on during the dissolution of Yugoslavia and because Serbia was much better at networking, which became a barrier between me and the other diplomats.”

Yet, the tragedy of her people, the Albanians, and of her country motivated her to never give up and to seek any opportunity to meet with diplomats and ministers. “I remember that in the beginning, they would not even receive me in their offices, but in corridors, or in the cafes at international conferences. Alternative spaces, corridors, and cafeterias became places for me to lobby,” she says. “I define this diplomatic journey as ‘from the corridors of diplomacy to the White House’.” Tahiri’s perseverance started to pay off. Washington, which had sent observatory missions to the country since the early 1990s, started to take Kosovo’s plight more seriously and its patronage helped Tahiri open more doors to advance her cause.

These open doors would not be enough if she couldn’t make a convincing argument but Tahiri managed to do just that. “I would encourage everyone to take on such a role but it is a difficult mission; it is possible to change international opinion if your arguments about what you are fighting for are coherent and consistent,” she says. Her talent of sticking to the principles Kosovo was striving for, but also leaving space to create compromise where it was possible, helped her – and her nation – gain ground.

Rambouillet

Her years of dedicated work as Minister of Foreign Affairs led to the cornerstone Peace Conference of 1999, negotiated in the French castle of Rambouillet, where the fate of her new country was decided. “In Rambouillet, we preserved the principle of Kosovo’s self-determination despite pressure from the Serbian delegation,” she recalls. “We insisted that, after an interim period, Kosovo has to have a mechanism to decide its own political future. We would only accept an interim agreement that left a door open for independence and placed Kosovo under a NATO protectorate,” she adds.

It was not an easy struggle, Tahiri says. Belgrade’s negotiators would claim that Kosovo had always been an integral part of the Serbian Yugoslav republic, while Kosovo’s delegates would respond that Kosovo had been a federal unit of the former Yugoslavia. “Few in the world at the time knew that Kosovo had a dual status in Yugoslavia, that it benefited from its position as a federal part of Yugoslavia and was not simply a part of Serbia. I had to discredit the Serbian narrative with arguments and present Kosovo's point,” she says.

In the end, the diplomatic mission in Rambouillet was a success. Kosovo received not only an implicit recognition that an independence referendum could one day take place, but also an explicit international pledge for Kosovo’s protection by a NATO peacekeeping force. Tahiri claims this was her most important diplomatic achievement by far, dwarfed in significance only by her signing the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Kosovo on 17 February 2008.

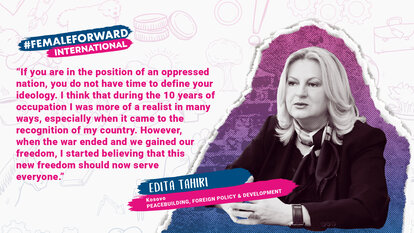

A realist in times of war, a liberal in times of peace

With the end of Serbia’s occupation of Kosovo and the return of normal life, this self-described ‘realist in the international realm’ has turned towards liberalism and domestic reform. How – and why – did this happen?

“Personally, I think that during the 10 years of occupation I was more of a realist in many ways, especially when it came to the recognition of my country. That’s because the international system is based on realism when resolving conflicts,” she says. “When the war ended and we gained our freedom, I started believing that this new freedom should now serve everyone. That idea led me to the ideals of liberalism and, to this day, I believe that equality of opportunity and the supremacy of the law are the basis of any democratic state and that government is there to serve the people.”

However, being a liberal woman in a relatively conservative Balkan nation is not an easy task. “From the beginning to a free Kosovo has been a transformational process, and I’d say now that it takes time for a real transformation towards real democratic values to take place,” Tahiri says. There have been many positive and progressive developments, like giving equal (and even preferential in some respects) freedoms to Kosovo Serbs and other minorities (“freedom should serve everybody, not only the winners,” Tahiri notes) and introducing gender quotas to boost female participation in politics. Some problems that seem traditional for the region remain, the most significant being, of course, corruption and the lack of accountability for the politicians in power.

“In the aftermath of the war, when my party, the LDK, began governing, corruption and autocracy appeared. That was something I could not change,” says Tahiri. To her, autocracy and corruption have remained part of the fabric of every government – even the ones that she was part of – during the first 20-odd years since Kosovo’s liberation, and no cure has yet been found. “Politicians come into politics in order to get more out of it than they give. This has been known since the time of [German sociologist Max] Weber. While I was Minister, I remained ethical and fought corruption”, says Tahiri. “I want to see more idealism in our political leadership. I want to see the idealism that we had when we founded the independence movement in 1989 and that carried on until we attained our independence, freedom, and self-determination. However, in the post-war period we seem to have abandoned idealism,” she laments.

Taking a direction of her own

Tahiri says how, after the end of the war, she was committed to democratic reforms in the LDK movement she had been part of for over a decade but her reformist efforts hit a brick wall.

“When the LDK independence movement transformed into a political party, I hoped that LDK would stick to the values and principles on which it was created,” she recalls. “Given that it was an elitist movement, I thought it could act as a leader of the post-conflict peacebuilding process in Kosovo. It is very important to create internal democracy in a political party and that was lacking in the LDK. Our system of values was undermined. After the war, instead of those who led during wartime taking higher office, you saw people of lesser merit suddenly climbing to the top,” Tahiri adds. She had to move on so she launched her own reformist project, the Kosovo Democratic Alternative (ADK), in May 2004.

From the start of her new political project, Tahari took the cause of gender equality to heart. “Personally, I never experienced any discrimination, although I was the only woman in the leadership of the independence movement,” she says. “However, in the post-war period the traditional barriers returned, this idea that power belongs to men, that women are not entitled to public positions. Women found themselves sidelined. Not me personally, because I already had strong credibility as a leader. But the picture was not good in terms of gender equality,” she adds.

Once she and the progressives around her agreed to oppose women being treated as underdogs, they acted. “We – women in politics and civil society – stood up for gender equality immediately after the war. We established a quota of 30 percent in Parliament after the first post-war election in 2000, becoming the first country in the Balkans to do so and a role model for the rest,” she says.

While she agrees that quotas are an artificial instrument, Tahiri notes that it helped expose more women to high-level politics and showed Kosovo’s society that without them in positions of authority, the country cannot hope to develop a real, working democracy. “Today, as we speak, Kosovo is better in terms of having women in government; the President is a woman, and Parliament has over 30 percent [female representation]. These are good achievements but challenges remain – we still have to build sustainable gender-inclusive systems,” Tahiri says. Her fight for gender equality and gender-inclusive peacebuilding continues at the regional level – she has been the leader of the Regional Women’s Lobby in South-East Europe (RWLSEE) for over fifteen years.

“I would like to see sustainable gender equality in my country and the world; I would say there is no real functioning democracy without the equal participation of women in decision-making,” she underlines, saying that women have to step up in the key areas of politics and civic activism, especially in peacebuilding. “When it comes to the formal peace processes and decision-making, discrimination continues,” the diplomat says, adding that she still remains the only woman in the Balkans to have led formal peace negotiations.

Kosovo and the world today

After the tragedies of war and occupation, where is Kosovo heading today according to this long-serving diplomat? “For Kosovo, our foreign policy is clear and it is Euro-Atlantic,” Tahiri underlines. “We don't want to see Russia in the Balkans, and neither do any of the new states that emerged from the former Yugoslavia except Serbia, which uses Russia as a Trojan horse. Our goal is to see the Balkans and Kosovo attached firmly to the West. Anything else is not an option,” she adds.

At the same time, she does not spare criticism about the role of the West, and especially that of the European Union, in the troubles that have engulfed the region during the past three decades. “To speak historically, after the Cold War, the EU failed to play an important role in the wars happening in the Balkans, despite them taking place in its own backyard. But the UN was failing as well. Only when the USA took the leadership role did the wars end and the conflicts were resolved.”

In more recent times, the EU’s role has improved, but remains dualistic, Tahiri reflects. “After the war, the EU played a much more important role, as it became one of the four pillars of state building at the UN’s mission in Kosovo and I appreciate the contribution of the EU to our economy and recovery,” the diplomat notes. At the same time, she is far from happy with the overall geostrategic approach (or lack thereof) that Brussels has taken.

“When it comes to geostrategic issues, the EU's failure is serious – not only vis-a-vis Kosovo, but with regards to the entire Balkans. In the past 20 years, the EU failed to consolidate a strategic approach towards the Balkans although all the Balkan countries (except Serbia) were determined join the West,” she claims, adding that the EU ought to have done more in order to integrate the ex-Yugoslav nations quicker, without allowing non-Western actors such as Russia, China, and Turkey to establish a foothold. “The EU needs to find a way to build unity in its foreign policy if it really wants to grow into an influential strategic player,” she concludes. She also states that the transatlantic block should strengthen its protection of the Balkan’s western orientation, which has weakened recently.

Hopes for the future

There is a lot Edita Tahiri can be proud of when it comes to the progress made by her nation during her lifetime – from an oppressed and sidelined people throughout the 20th century to a free, independent country today. What future does she envision for her nation now?

“There are many challenges ahead of us, first of all – achieving economic progress and opening job opportunities so our youth can fulfil its dreams in Kosovo and not outside it. The emigration of our young generation is the bane of our society. At the end of the day, the present and future of our nation rests with the energy of our youth,” Tahiri says, adding that retaining its younger citizens ought to be Kosovo’s strategic goal.

“In foreign policy, our strategic objectives are the integration of Kosovo in NATO, the EU, and the UN while also improving neighbouring relations, including the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue,” the diplomat says, adding that the latter ought to conclude with a mutual recognition of the two states under current borders. “And third is to finally close the chapter of wars and hostilities and to start the next one – of peaceful relations,” Tahiri concludes. “We should not leave this burden to the next generation.”