#FemaleFowardInternational

Remaking a fractured society

How do you survive in the world of politics as a trained architect? What do you do as a woman if male parliamentarians comment on your looks more than on your speeches and the bills you propose? Is it possible to change the narrative in a fractured political system still preoccupied with the traumas of war and the past glories of 70 years ago? Nasiha Pozder, member of the Federal parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Nasa Stranka (meaning “Our party” in Bosnian and Serbo-Croatian), can say a lot about each of these questions.

Holding a PhD in Architecture and Urbanism and having a successful academic career were not enough for Pozder, who realized that without changing her country fundamentally, both she and her daughter would not have places in it in the future. So, in 2011 she accepted an invitation to join a movement that started in 2008 as an attempt by foreign-educated, liberal, and left-leaning Bosnians to take down the status quo that they considered corrupt. By that time, she was a known name in the civic movement circles of her native Sarajevo for her criticism of controversial urban development ideas and her involvement with sustainability initiatives.

An urbanist in the world of politics

“They wanted someone with my profile, because I was pretty active in the urban scene of Sarajevo, talking about corruption in urban life, trying to raise my voice on urban issues and to say that it's not just investors who are to blame, but also politicians and urban planners,” she shares. The timing of this invitation could not have been worse though – at the time, Pozder was completing her doctorate, raising a child, and taking care of her sick father. “It was a really terrible time for me, but on the other hand it was a question of whether I should stay here or go – at the time I was invited to work at the Technical University of Delft in Holland. But I decided to join Nasa Stranka in 2011 and try to change something here.”

From then onwards, it was a rollercoaster ride for the architect. First, it all started with a backbencher position, organizing the local party structure in Sarajevo. After she brought the party success in the municipal elections, Pozder got drafted onto the regional board of the party, and in a year, she became the vice-president of the branch. It all seemed like a surprise to Pozder herself. “I was like "how did this happen, what am I doing here? I am not a politician; I don't want to be a politician." But I stayed, and for two years I worked on the internal politics of the party, making the political platform for the 2014 general elections. I was also a candidate, but not for an electable position, because I still wasn't sure if I wanted to be that kind of professional politician. I was satisfied being the kind of person who writes about what they know best.”

Changing dominant paradigms

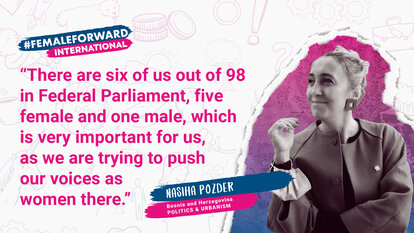

Yet, after she climbed even further up the party ladder – and while what was still predominantly a civic movement was gradually turning into a “real” party - the cornerstone 2018 general election took place and Nasiha Pozder became one of the 6-person strong representation of Nasa Stranka in the House of Representatives of the federation. Nasa Stranka set a new precedent when, in a country where women were less than 20% of the representatives, their group was dominated by women 5 to 1. Overall, the percentage of female candidates elected was above 60%. And that is not all that puts them apart from the other parties. “We are all pretty young, we are also mixed in terms of nationality – Serbs, Bosniaks, others... and that was not the idea – it just happened through our work and the ideology that we represent.”

In a country still divided by the scars of the 1990s war and ethnic cleansing, that is a big deal. But it is also the least one could expect from a movement launched by award-winning director Danis Tanovic, who captivated audiences at home and abroad with his 2001 anti-war epic “No Man’s Land.” To Pozder herself, it was extremely attractive that intellectuals and members of the cultural sphere decided to join and take responsibility for the future of the country into their own hands – a very rare move for people who prefer to criticize. “Intellectuals don't want to join parties on the operational level, they want to support it, or to write you on Facebook and tell you are doing everything wrong and ask you how you can even dare think you can negotiate with the old socialists... But when you invite them to join, they usually say they don't have time, or they don't want to get their hands dirty.”

The haunting spirit of inefficiency

Once she made it into high-level politics, however, Nasiha Pozder saw a lot not to envy her for. “I just had a coffee with my colleagues from the faculty and they were saying how discouraged they are to live here and see all the problems we have. And I said – yes, it is even more discouraging when you are inside parliament and there is not much you can actually change, but there is no way to quit,” she says. What motivates her to keep going – at least until the next elections – is the possibility of Nasa Stranka growing and serving as an example for the rest of the country about how synergy on the local, cantonal, and federal levels can actually make things work.

At the same time, she does not hide her worries about the future direction of the party as it grows. “We are no longer sure that most of our members are devoted to our ideas. Maybe they are approaching us because they see us as a spark of hope, and are not even thinking about our agenda, about our political and ideological background, which is really hard for us to handle. Because we really want to stay a progressive, liberal, green party,” she says. This brings her to the personal ideological conundrum she faces being part of a liberal party (and a member of ALDE for five years now) and having green convictions. Yet, she understands that it is counterproductive to split hairs – and parties – in the Balkans in order to achieve ideological purity. “I stick to our party’s green wing, but I find myself aligned with some ALDE parties like D66 or the Centre party from Sweden that are liberal, but are also green enough,” she says.

Tired of history, eager for the future

For Pozder, at this point getting too particular about one’s own political beliefs is secondary to her greater mission in politics – making sensible arguments that focus on the problems which are really important for the country. “We here don't have a party that is similar to ours – we have socialists, who are actually a product of the ex-communist party of Yugoslavia, and we have the nationalists as a right-wing party, which is not even right-wing in the general sense. They can be very centrist, but often invoke emotion and bring up the war and you know how that goes.”

She says she is tired of the political debate in the country revolving only around conflict – either the recent one or the Second World War – instead of resolving big issues, like the one about ethnic representation. “We cherish the idea of anti-fascism, but we are talking about looking to the future and closing the gaps that divide our society, how to change the constitution so that all people have the right to be elected for example, but more important, to be equal. For example, our President is an ethnic Serb – he can't be elected president of the country because he is a Serb from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and not the Republika Srpska.” Pozder says that her party already had tried pushing through a constitutional amendment that would change this discriminatory law in the Federal Parliament and will continue doing so in the future if they are in position of power. Actually, they have already passed a similar amendment that allowed people who do not identify with any of the large ethnic groups in Sarajevo to become president of the canton.

Another important issue that Nasa Stranka wants to push forward is cutting down the unnecessary and overlapping parts of the administration of the country, which consume its already scarce public resources. “Politics in Bosnia and Herzegovina is a really good "factory" where you can find a job. Every fourth resident works in the administration. It is a large system where you can make money without working a lot – or at all. Our main goal is to try to dismantle this huge apparatus that we have.”

This has proven a controversial idea because of the relative success of the Dayton Agreement – the 1995 deal that sealed the peace in the war-torn country. It has practically been the basic law that ensured a balance of representation and power of the warring ethnic fractions in the Federation. To Pozder, however, it is time that the agreement is revised. “Everything has changed in these 25 years in the country except the constitution.”

To her, the current way the system operates produces huge and useless inefficiencies, feeding a corrupt and largely ineffective bureaucratic class. “In Dayton we agreed that we have two state entities, in one of them ten cantons, and each canton has their own different ministries, at least ten of them. For example, one of the cantons has only 23,000 citizens, but it has 10 ministries, an assembly with 30 members, and a Prime Minister – it is a huge operation. And this canton practically overlaps with a city, which has nearly the same inhabitants, but they have their own administration – mayor, councillors... This is what we want to change,” she says. Her dream is to have a “normal” Bosnia and Herzegovina divided into regions for geographic and economic reasons instead of along ethno-nationalist lines.

The additional complication of being a woman

On top of all that, Pozder also must endure what it is like being a woman in politics in the Balkans. Like all of the Female Forward ambassadors, she is thick-skinned and confident enough to snub most of the sexist and misogynist remarks that come her way. Yet she can well understand that what women have to endure by entering public life may be the primary reason for their underrepresentation. “I was fighting for this important piece of land in the city of Sarajevo back when I was an activist, and I was called “toothy” by my opponents. It was not important what I was talking about, it was about mocking how I look,” she shares.

In addition, during her first days in Parliament some of her male colleagues from other parties commented more about what she wore rather than what she said from the tribune. “But this lasted only during the beginning – very quickly we were listened to.” Another expression of casual sexism she remembers is how the speaker of parliament turned to male MPs and addressed them as “Mr” and their surname, but to Pozder and her female colleagues by their first names – by saying “Ms Nasiha.” “Excuse me, I am not Nasiha for you, I am also your colleague, Member of Parliament Pozder,” she told him.

According to Pozder, these attitudes come from the traditional, patriarchal culture that dominates Bosnian society. “I was lucky that my father wasn't that kind of person and he supported me even during the war, because he knew what I was working towards. That is actually why I started to raise my voice for the position of women in society, because I understood that my luck is not something that everyone has. My position in the academy and in politics is something that gives me not only opportunity, but also an obligation to repeat that message – that women in society have to raise their voice.”

She is, however, well aware of how daunting this task is. On the one hand, there is the patriarchal culture that dominates most parties in the country and prevents the implementation of the equal representation quota system which is in place. On the other, there is the backlash from conservative female representatives from the traditional parties that makes Pozder doubt the notion that there is anything specifically feminine about female leadership. “I think that women can be more sensitive, often more reasonable, looking for compromise… but it is also not something that we can generalize – I have a hard time talking to female colleagues from the right-wing parties, but that is their position in the party talking. When they get a task from the party, you don't hear their female voice, but hear the party voice.”

What keeps Nasiha Pozder going, despite all inefficiencies and deficiencies of the political system in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the hope that her work would contribute to a better future for all, including her own daughter. “I have my daughter and my mother with me, we decided to stay here, I really don't want to lose my time not being with them if I am staying in Parliament and not seeing results. We are showing in my canton that there is reason for optimism, and to hold on a bit longer.”

Follow more stories on female empowerment with #FemaleForwardInternational and in our Special Focus on the website.