Germany

Victory, Tragedy and the Future of Freedom

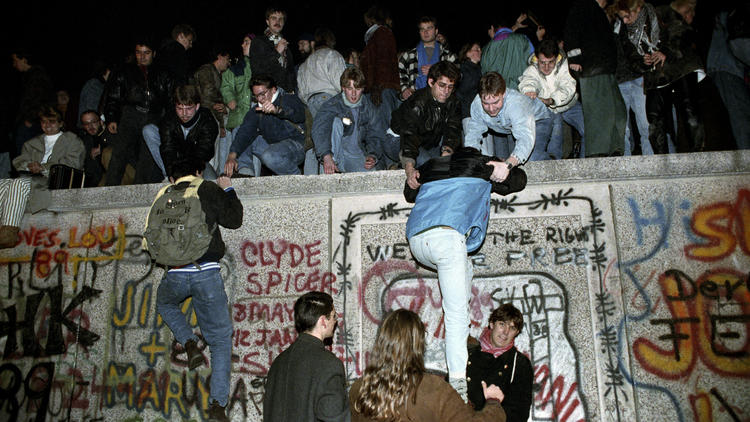

The fall of the Berlin Wall exactly 30 years ago was a great victory for freedom. Until today the feeling of happiness remains. It was shared by most people in Germany. All those, who have experienced the feeling, will never forget the moment - and that is a good thing because the memory of it carves freedom into our hearts. Tears of emotion still come to me these days when I see the television pictures of that time - and I'm certainly not the only one who feels that way.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was the symbol of liberation from the dictatorship of Soviet socialism. "Ein Jahrhundert wird abgewählt" is the German title of a book by Timothy Garton Ash that appeared only a few months later. And the fall of the Berlin Wall was the human climax of this deselection, even though it had dragged on for over a decade via Solidarnoç in Poland, Glasnost and Perestroika in the Soviet Union and the opening of the border in Hungary. However, it was not until the fall of the Berlin Wall that it became clear that freedom had won.

Few noticed, however, that a tragedy of freedom was also beginning to unfold politically. From the 9th of November 1989, the East Germans were not only free but also mobile - as a natural part of freedom. Everyone could seek their future in the West. Especially for young, well-trained top performers, the temptation was great to work as German citizens in the West - for good wages in healthy companies in an intact consumer world.

This temptation put politics under enormous pressure. They had to prevent mass emigration without building a new wall with visa requirements and border controls. Everything that was missing in the East had to be delivered quickly and trustworthily. The result of this pressure was a monetary and economic union plus political unity, as well as expensive reconstructions in the East and rapid privatization. We know the result: a difficult dry spell of adjustment, but also of growth, which led East Germany economically to where it stands today: with wages three times higher than those of its eastern neighbours in Central Europe, but still around 25 per cent lower than in the West.

In this process, many mistakes have undeniably been made, large and small. These must be openly discussed and analysed by science. And this has been happening for a long time, among other things after the opening of the Treuhandanstalt files as part of a project by the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich/Berlin, which is financed by the Federal Ministry of Finance. Eventually, it will be possible to come up with balanced judgement.

In the meantime, however, there is a possibility that myths will become entrenched. At the moment, work is being done mainly on the poles of the political spectrum, left and right. The tragedy of freedom is being completely overlooked. Politicians after 1989 are blamed for the fact that the process of adaptation was difficult and has not yet been completed. Thereby the catastrophic state of the DDR's economic heritage is deliberately played down.

The result is a kind of new dagger thrust legend: The West was the first to ensure with German unity that the East did not get off the ground economically. This is a myth that could poison the political climate in Germany in the long-run. More importantly, it could endanger the future of freedom in Germany. In this world view, the closed society of the DDR was the more pleasant place to live than united Germany. The fall of the Berlin Wall became the starting point for misery, similar to the surrender of the (allegedly unbeaten) German army to the Allied forces in the Weimar Republic.

Fortunately, we are far from having reached the point where such an interpretation of German unity would prevail. However, the political debate on this issue is very alarming. After all, anyone who blames freedom for misery, will hardly be prepared to defend freedom. This is something we must counter.