Freedom of Press

I will have a drink for journalism in Mexico

A mexican musician called Sabino has a not very uplifting song about the need for a drink in any circumstance. He sings: 'My girlfriend left me and I got drunk; I found a new girlfriend and I got drunk (...) I passed an exam and got drunk, I failed an exam and got drunk.' It's not poetry but it's true.

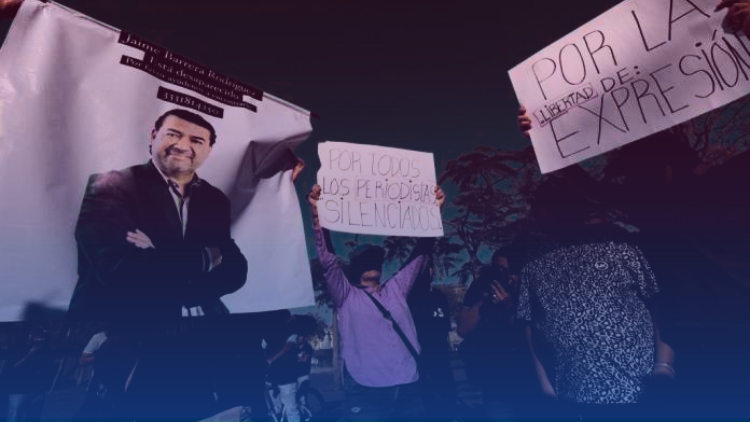

I belong to a generation that turns to liquor, beer, or a glass of wine to celebrate, to ease pain, to bear fear, and to contain great joys. Yoga and meditation are better, but for an emergency (including earthquakes), I turn to a drink, and that's what I did now that fear settled in my stomach upon learning that journalist Jaime Barrera had been kidnapped.

The more than 30 hours he spent handcuffed, blindfolded, on the floor of an unknown place, he must have thought he would die. We didn't dare say it out loud, but his colleagues, friends, and family (I'm sure everyone), also thought we wouldn't see him alive again. Additionally, my imagination played tricks on me and didn't give me scenes of Jaime sitting, eating, waiting to be rescued or executed. The scenes I constructed were much more painful.

Jaime Barrera is a respected and beloved journalist. He is a serious, professional journalist, whose friendship I value having. When we were young, we even got drunk together as only young people do. Well, he didn't, but those of us who hung out with him did. He drank and never got drunk, and the next day he was as fresh in the newsroom as if he had slept his 8 hours and gone to the gym.

His resilience was legendary. Today it will be more, for much more important and substantive reasons. Today Jaime returned from a long, heavy, dreadful night, and not a single day passed before he lent his valuable testimony to the many colleagues he has in the many Mexican media outlets.

The difference is that he doesn't laugh or joke, but besides that, Jaime strives to have a record of what happened to him. His interviewers, all his friends, treat him with caution but lead him to remember what happened and he does not refuse. He tries to catch every detail. Some men forced him to go with them. They did it with an already known operation: encapsulating his car with a vehicle in front, another on the side. They blindfolded him, put him in the back of the vehicle, and took him away. They handcuffed him. They hit him with a board. They wanted to know who asked him to write what he wrote (a column about a town where people publicly honor the criminal leader). They told him to back off. They threatened his family. They released him more than 30 hours later in the street.

Jaime, handcuffed, asked for help in a neighborhood store. The girl made the necessary calls and a little later the National Guard escorted him home, to his family.

Today Jaime is back and I, like Sabino, have another drink. A drink for the fear I had for his life, a drink for the fear I now have for all my colleagues in Jalisco, for the fear his radio team has, for the fear his team at Televisa has, for the fear his colleagues at Canal44 have, for the fear of all my journalist colleagues who doubt about writing what they were going to write. A drink for the fear Jaime will have from now on, even though he is a brave journalist who always ends up whole. A drink of joy because I will see him again, but also a drink of fear because what we experience in Mexico is not freedom of expression. How scary it is to write about cartels, about the disappeared, about the murders, about crime, about security strategies. That's why a drink is needed.

________

Ivabelle Arroyo Ulloa is a political analyst and Mexican journalist.