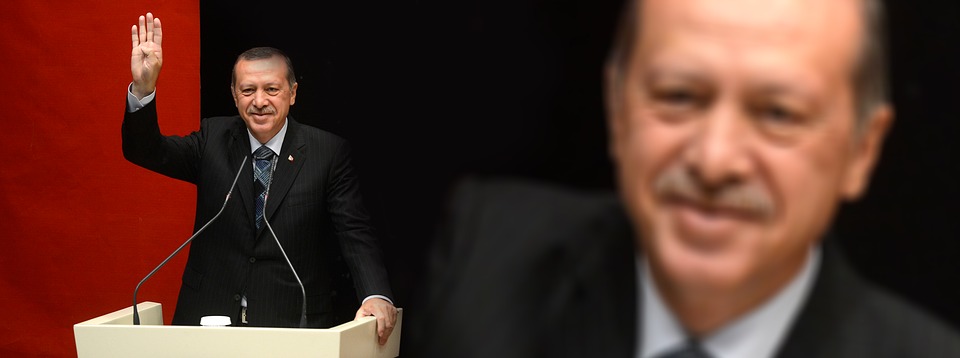

Erdoğan's Anointment: ‘New Turkey‘ Proclaimed

The Republic of Turkey, almost a hundred years old at the time, underwent an unprecedented historical departure on 9 July 2018, at 15:30 local time: with the inauguration of the former and current President, Erdoğan, Turkey is now officially a presidential republic. The office of Prime Minister has been abolished; the Prime Minister's powers and responsibilities have been transferred to the President whose authority has been greatly expanded. Erdoğan is head of state, head of government, party leader, and chairman of numerous administrative commissions, all at once. Although Hungarian political scientist András Körösényi had Hungary in mind when he coined the term ‘Fuhrer democracy’, the expression is easily applicable to 2018 Turkey as well. Erdoğan himself frequently speaks of a ‘New Turkey’.

Cumhuriyet, a newspaper critical of the government, called the new system ‘worse than a state of emergency’ and denounced the comprehensive expansion of the powers of the President. The formal transition to the new system took just under half an hour. Erdoğan's performance of the ceremony was mechanical – he took the podium and promised to uphold democracy, the rule of law, and ‘the principles of laicism’ in accordance with the set formula of the oath of office. The Members of Parliament of the AKP, the ruling party, rose to applaud, as did the nationalists of the MHP. The opposition remained seated. Some – the chairman of the secularist, Kemalist CHP – had failed to attend altogether. At the conclusion of the short ceremony, CNN Türk displayed an insert: ‘The new system has officially entered into force’.

In his first speech after his inauguration, Erdoğan promised a new beginning: ‘The system we leave behind has caused political, social, and economic chaos’, he proclaimed in front of an audience of 6000 in the presidential palace in Ankara. Erdoğan had arrived at the palace, together with his wife, Emine, in a limousine decorated with roses, and had been greeted by a 101-gun salute. Turkey was entering a new era that would see improvements ‘in every area, from democracy to fundamental rights and liberties, from economy to great investments’. Erdoğan, a master at alternating tension and reassurance, addressed the world in his usual style: moralising, patronising, triumphant. He wanted to be the President of all Turks. Intoxicated by his own power, he also reiterated his campaign promise to make Turkey one of the world's foremost economic powers.

Erdoğan's Inauguration Ceremony

More than 30 heads of state or government had travelled to the capital to attend Erdoğan's inauguration; the ceremony was half festival, half G20 summit. Guests included Dimitri Medvedev, the prime minister of Russia, Nicolás Maduro, the Venezuelan autocrat, and Omar al-Bashir, the Islamist President of Sudan, a man who has risen to power in a coup d'état and is wanted for arrest by the International Criminal Court. Europe was represented by Viktor Orbán, the Prime Minister of Hungary and a self-professed anti-liberal, and Dimitri Avramopulos, the EU Commissioner for Migration. Many Western democracies merely sent their local ambassadors, yet another sign bearing witness to the rapid estrangement between Europe and Turkey.

The German Federal Government was represented at the inauguration by former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder. A Foreign Office spokesman explained that Schröder had not been tasked with consultations but was attending merely as ‘a matter of protocol’. The Turkish national news agency, Anadolu, referred to Schröder as a ‘special friend’ of the President.

A mere 24 hours after his inauguration and the subsequent traditional visit to the Atatürk mausoleum, Erdoğan presented his cabinet. It consists of sixteen ministers – ten fewer than previously. The streamlining is supposed to consolidate responsibilities and to make the bureaucracy more efficient. Speculation regarding the composition of the new cabinet has been afoot for some time. It came as a surprise too many that Devlet Bahçeli had been passed over – Bahçeli is the chief of the MHP, the right-wing nationalist coalition partner of the AKP, and Erdoğan's unofficial kingmaker.

Erdoğan's closest advisor and spokesman, Ibrahim Kalın, is likewise missing from the list of ministers, even though he had been rumoured to become Minister of Foreign Affairs. Mehmet Şimşek, previously the Deputy Prime Minister for Economy and Finance, is missing as well. Şimşek was reputed to be the last representative of what used to be the AKP's liberal wing; he is said to have fallen out of favour with Erdoğan as of late. Foreign investors had hoped that Şimşek would remain on the cabinet as a guarantor of economic rationality.

The new man at the helm of Turkish financial and economic policy is Berat Albayrak, previously the Minister of Energy; Albayrak married to Erdoğan's oldest daughter, Esra, and is widely considered Erdoğan's heir apparent. Albayrak differs from both Şimşek and from his predecessor, Naci Ağbal, in that he favours looser monetary policy. Low interest rates and generous public investments are supposed to stimulate private consumption. The cabinet, chaired by the President himself in his capacity as the head of government, no longer includes a ministry of economic affairs. Mustafa Varank, a career bureaucrat and close confidant of Erdoğan's, has taken charge of the Industry and Development portfolio. Ruhsar Pekcan, a woman obscure even in Turkey, is the new Minister of Commerce and thus in charge of foreign trade. The 60-year-old electrical engineer used to head a section of the Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey (DEIK), an institution of considerable importance.

Future economic policy will likely be shaped by Albayrak. It should be interesting to see which track he will take. On the heels of years of growth stimulus financed by debt, the country is due for a downturn. In theory, it would have been Şimşek's responsibility to soften the slowdown – through a significant increase in key interest rates, among other measures. Erdoğan is a noted opponent of interest rate hikes, but Şimşek won against the President in the matter. It is doubtful whether Albayrak will be able to assert himself in the same way.

The independence of the central bank, which Erdoğan has repeatedly attacked in the past, is more endangered than ever. Albayrak's first statement as the new Minister of Finance did not bode well. The independence of the central bank is ‘not a topic for speculation’, Albayrak declared; he then added that ‘one of our most important goals for this new era is a central bank that is efficient as never before’. His meaning became thoroughly clear mere days later: President Erdoğan issued a decree vesting himself with the authority to appoint the president and vice president of the central bank. In addition, he shortened the term of office of the country's current two ranking central bankers from five to four years. In the past, the President used to appoint the chief of the central bank with the advice and consent of the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister. The appointment also had to be confirmed by the cabinet. The new decree, consistent with the general philosophy of Erdoğan's new order, does not mention any cabinet members other than the President himself.

Albayrak's former office as the Minister of Energy is taken over by Fatih Dönmez, who had been leading the Istanbul gas works since 1994, the year Erdoğan became the city’s mayor. Mehmet Ersoy, the new Minister of Tourism, is a product of his industry: together with his brothers, the 50-year-old built and ran the country's largest travel operator. Ersoy is taking over from Numan Kurtulmuş, a confidant of Erdoğan's. The new Minister of Family Affairs on the other hand, Zehra Zümrüt Selçuk, is an unknown quantity. The only woman in the cabinet besides Ruhsar Pekcan, her portfolio also includes labour and social affairs. The new Minister of Defence is none other than Hulusi Akar, formerly the chief of the general staff of the Turkish armed forces – an all-time first in the country's history. In past decades, the Ministry of Defence used to be led by civilians with no personal power base in the military. Akar, 66 years old, had caused a stir in the election campaign when he was seen calling on former President Abdullah Gül in his garden. Parts of the opposition had hoped that Gül would stand as a candidate. Shortly after Akar's visit, however, Gül announced that he declined to run against Erdoğan. Akar is reputed to be a loyal supporter of Erdoğan's.

The President retained Akar as his top general after the failed coup in the summer of 2016. Akar's successor on the general staff is Yaşar Güler, previously the commander-in-chief of the land forces, whose role in the coup has been the subject of rumours. The office of Vice President, last not least, is being assumed by Fuat Oktay, another trusted friend. Oktay has played a role in implementing the transition to the presidential system. The fact that there is only one Vice President comes as a surprise.

Erdoğan's list of minister includes four newly minted Members of Parliament removed from the legislature and promoted to the cabinet. Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, for example, had been confirmed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs; he had been holding the office since November 2015. The Ministry for Relations to the EU, originally created in 2011, has been disbanded and replaced by a "General Directorate for Relations to the EU", an adjunct of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The change is widely seen as an admission that accession negotiations have come to a halt for the time being. Süleyman Soylu, a proponent of law and order, remains in office as the Minister of the Interior. Abdülhamit Gül remains in office as the Minister of Justice. As the new constitution stipulates that Members of Parliament cannot hold positions in the executive branch, the four politicians had to resign from the legislature.

In addition to the cabinet, Erdoğan has created nine new advisory councils (‘kurul’) and four other new offices (‘ofis’). The new institutions appear to be meant as think tanks providing advice to ministries, covering a number of areas of policy and administration. In particular, they are tasked with promoting bureaucracy reform. Organisationally, they answer to the President.