Mu Sochua: The Brilliance & Resiliency of the Gem of Cambodia

Mu Sochua

©Cambodia is a paradox. The Khmer Empire, one of greatest civilizations of Southeast Asia, produced some of most magnificent manmade monuments in history. Angkor Wat is the triumph of art and architecture as it is of faith and genius. But Cambodia has a dark side: the bloody legacy of the Khmer Rouge resulted in one of the worst genocides of recent history.

Cambodia is both rich and poor, young and old, free-spirited and repressed. In Cambodia, one should learn to expect the unexpected.

“There’s no gentle way to put this. Cambodia messes with your mind,” journalist Jen Cowley put it succinctly. “It takes your western judgements and perceptions and turns them on their head. Then it takes everything you know about human nature and challenges you to apply that knowledge to this country’s past, present and hope for the future...and still not fully understand the psyche of this remarkable little nation of contradictions” (Cowley, 2013).

However, the tyrant of Cambodia is more predictable. He behaves like most dictators who are his contemporaries from this region like Suharto and Ferdinand Marcos. But they are all dead and gone. Hun Sen is not only very much alive, he is very much in power. He is currently the longest reigning national leader who was first elected Prime Minister on 14 January 1985.

But not too long ago, he took it one step further. Instead of resorting to the usual electoral fraud to maintain himself in power as he had repeatedly done in the past, he took the short cut and simply asked the supremely subservient supreme court to dissolve the opposition party since it was predicted to win, despite the manipulation of the ruling party.

And only in enigmatic, paradoxical, and predictably unpredictable Cambodia can someone as courageous, intellectually astute and steadfastly principled person like Mu Sochua can earn this rather discombobulating distinction, both noble, for her part, and ignoble, for the part of the rulers, at the same time. And that is, being the first woman to become Minister of the Ministry of Women.

Abhorred by tyrants, loved by her people, respected by her colleagues and recog- nized globally as a champion of democracy and women’s rights, Sochua was invited to keynote the Oslo Freedom Forum on 29 May 2018. She started her speech with the story of her youth, then and now, forced to exile as matter of life or death—then, because of the genocidal Khmer Rouge, and recently, because of the tyrannical Hun Sen. Hun Sen himself is a remnant of the Khmer Rouge, the present being an unfortunate continuation of a tragic past.

“It was a warm afternoon of June 1972 when my sister and I left to study in France. We were young, we were scared but we were relieved that we could leave Cambodia. The Vietnam War was spreading into Cambodia very rapidly. From 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia (which) became the Killing Fields...Close to two million lives were lost. My parents and relatives were among those starved to death or killed by those hardcore communists.”

Sochua grew up in a comfortable middleclass household in Cambodia. “My mother was the breadwinner despite having only three years of education,” Sochua narrated. She was in exile when her parents died. Five years after her mother’s disappearance, her father who used to be a businessman died of malnutrition in 1979. War is a great equalizer and in the case of the Khmer Rouge, the educated were specifically targeted. “I never knew how my parents died so there’s no closure in my life.”

“Her painful past drove her to want to help those from her war-torn country,” Berkeley Social Welfare (n.d.) noted. “Sochua did fieldwork at the Alameda County Health Care Services, Asian Program in Oakland during 1979 to 80. Her second-year placement was at the YMCA in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco, with the Cambodian Project” (Berkeley Social Welfare, n.d.). After Berkeley, Sochua returned to Asia. According to the Heroine Collective, it was in 1984, while working with Cambodian refugees at border of Thailand, when she met her American husband, who was also working with refugees and eventually went on to work with the United Nations (Karlins, 2015). She and her late husband, Scott Leiper, have three daughters.

“In 1989, she moved back to Cambodia and with her newly acquired social work skills, started Khemara, an NGO dedicated to fighting for women’s rights (and) began tackling some of the most difficult issues plaguing Cambodian society, such as sex traf- ficking and domestic violence,” according to Berkeley Social Welfare (n.d.). Khemara is the first Cambodian non-government organization working for the empowerment of women and children by engaging communities (Khemara Cambodia, n.d.) From civil society, a common background for many women featured in this book, she entered politics. She won a seat in the National Assembly in 1998, representing Battambang.

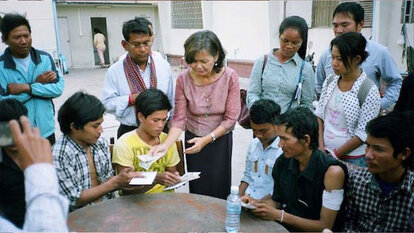

As parliamentarian and minister, “Sochua fought to end worker exploitation, curb sex trafficking, and developed Cambodia’s first major legislation on violence against women. Moreover, in 2002, Sochua started a campaign to get women involved in politics. In form not traditionally seen, she traveled to the countryside, talking to villagers, face to face, encouraging rural women to run so that they could represent themselves and their communities. Largely because of her efforts, 25,000 women ran for office, and nine percent were successfully elected” (Robinson, 2018).

In 2005, Sochua was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to stop the trafficking of women in the Cambodian and the Thai sex trade; and in 2007, UC Berkley pre- sented her the prestigious Elise and Walter A. Haas International Award. (Berkeley Social Welfare, n.d.) During the Human Rights Day of 2009, she received the Eleanor Roosevelt Award for leadership in human rights. These are just some of the many global awards that she has received. She is not lacking in international recognition, but it is the love, support, and conviction for shared principles of her countrywomen and men that keep her going.

The author first met Sochua in January 2002 in Bangkok during the First Political Party Strategies to Combat Corruption Workshop, a joint project of the Washington DC-based National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) and the Council of Asian Liberals & Democrats (CALD). He was CALD Executive Director during that time but Sochua was not a CALD member as she was with another Cambodian political party, the royalist FUNCINPEC which was a member of the ruling coalition. Even then, he already sensed that she was too principled and too unwavering in advocacies close to her heart like democracy, human rights and gender equality for her to be associated for long to the tyrannical and misogynistic Hun Sen.

Disgruntled with massive government corruption, Sochua resigned as minister in July 2004 and immediately joined the opposition Sam Rainsy Party (SRP), a CALD mem- ber-party since 1999. Sochua would become Chair of the CALD Women’s Caucus from 2009 to 2011. When the author heard the news of her resignation from Hun Sen’s cabinet, the words of the late Philippine President Manuel Quezon echoed in his mind: “my loyalty to my party ends where my loyalty to my country begins.”

From being part of his cabinet, she became one of Hun Sen’s most vocal and eloquent critics. Mild-mannered and soft-spoken, Sochua has always been convincing and credible. And here lies another paradox: in her firm but hushed voice, she becomes more piercing in her condemnation of the injustice and graft committed by the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). Like the muted candlelight of the SRP logo, her words flicker in the dark.

Since the author met him in 1999, Sam Rainsy (2015) has always referred to Cambodia as “a façade of democracy” that is “ruled by one dominant political party that has little tolerance for dissent; media is restricted, and the freedom of peaceful assembly is often curtailed; and the electoral system is manipulated to favor the ruling party. The curtail- ment of human rights and civil liberties continues and done with sheer impunity—all in the name of national security.”

But such tyranny did not remain unopposed, not just by politicians but more im- portantly, by ordinary citizens. “In 2009, Hun Sen insulted me in public and I took him to court,” Sochua recounted during the recent Oslo Freedom Forum. “And he took me to court and I lost, of course. However, each day that I went to court, thousands of women and men marched with me to court and they mobilized funds to pay for my fine. Justice always prevails.”

These were ordinary citizens who braved arrest by merely showing solidarity with an oppositionist and though financially wanting themselves, they gave little of what they had for something as alluding as justice.

On 17 July 2012, the Human Rights Party of Kem Sokha and the Sam Rainsy Party would merge as the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). As Rainsy was in exile during that time, CNRP was founded in Manila at the CALD office. Sochua who was at the Manila meeting would serve as Vice-President of CNRP until its dissolution on 16 November 2017.

On that day of infamy—November 16, 2017, the facade of democracy totally peeled off. Since then, Cambodia is under an undeclared Martial Law. “Democracy was on trial this week in Cambodia, and it lost,” Sochua wrote in The Guardian as she chastised the complete subservience of the Supreme Court to Prime Minister Hun Sen when it dissolved CNRP and banned more than a hundred of its members from elections in the next five years (Sochua, 2017).

“As the only opposition party capable of mounting a serious challenge to the ruling party in national elections – scheduled for July – the CNRP posed a threat to the continu- ance of more than three decades of Hun Sen’s brutal, strongman rule,” Sochua argued in the same opinion piece. “The mounting fear of losing in a genuine vote motivated this de- cision and spurred an unprecedented crackdown that has seen my party’s president, Kem Sokha, imprisoned; prominent NGOs and media outlets shuttered; and over half of CNRP lawmakers – including myself – forced to flee the country. In pursuing this course, Hun Sen has proved himself nothing more than a dictator bent on remaining in power, no matter what the costs.”

Hun Sen thinks and behaves like the archetypal dictator, whether real or fictional. In The Autumn of the Patriarch, it seemed that novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez was describing the Cambodian strongman when he talked about the General, his main character, “...as he discovered in the course of his uncountable years that a lie is more comfortable than doubt, more useful than love, more lasting than truth...”

Hun Sen came to power during the advent of people power movements that toppled tyrants in the Philippines, Eastern Europe, South Korea and Indonesia. He remains resilient and is likely approving of the resurgence of populism and even authoritarianism in the Philippines, Thailand, the United States and even Europe.

What now for Mu Sochua and Sam Rainsy who are both in exile, and Kem Sokha who remains incarcerated, trapped in the global political arena characterized by the plunging popularity of liberal democracy and the corresponding rise of populism and despotism, and exacerbated by the Post-Truth Era? What Archibald MacLeish famously said about seven decades ago still remains relevant today: “How shall freedom be defended? By arms when it is attacked by arms, by truth when it is attacked by lies, by faith when it is attacked by authoritarian dogma. Always, in the final act, by determination and faith.”

In his many travels to Cambodia, not just in the capital Phnom Penh or in touristy Siem Reap, and especially during assemblies and visitations conducted by the opposition, the author has observed something about the Cambodian. Majority of the Cambodians are poor, and as result, most of them received very little formal education. But he sensed in them this passionate yearning for democracy. They might be poor and impoverished, but the first things they asked for were abstract concepts such as change, justice and free- dom. The author was convinced and remains convinced that the Cambodian is innately aware of the correlation between democracy and development—both of which Hun Sen is incapable of delivering. Cambodians know they are poor because they are not free.

Hun Sen’s rallies have always been well organized—his supporters provided with transportation, food and even entertainment. Those who attend opposition rallies, on the other hand, go there on their own volition without anything given to them. Nothing but hope, and the distinct possibility of better lives.

“History has taught us that you cannot suppress an idea whose time has come, and more importantly, you cannot suppress that idea by the very means it is further nurtured,” Rainsy asserted. “Every human being is born free, ought to be free and is willing to fight to be free. And that every society which consists of individuals who are free—whether in fact or in mere aspiration—will only be satisfied in a nation that is open, humane, inclusive, just and tolerant” (Sam, 2015).

“They can detain us physically, but they can never detain our conscience,” Kem Sokha, prisoner of conscience, asserted.

“Democracy may have lost this week, but it was not a knockout blow. Democracy will not die in the hearts of the Cambodian people,” Sochua was emphatic in her 2017 op-ed piece in The Guardian. “The government may have officially dissolved the opposition party, but it cannot do the same with the three million Cambodians who voted for change in the last elections. It cannot erase the 1.5 million Cambodian migrant workers abroad, who long to return to a country that is democratic, prosperous and free. It cannot abolish the hopes and expectations of Cambodia’s ten million young people, who dream of a promising future, free from corruption and oppression.”

Again, during her Oslo Freedom Forum keynote address, Sochua cited an old, Cambodianproverb: “Menaregoldandwomenarejustawhitepieceofcloth.” Tothis, Sochua rebutted, “I say, no way, we have to change this proverb to ‘men are gold and women are precious gems.’ (Women are) the gems of Cambodia.”

References

Berkeley Social Welfare (n.d.) https://socialwelfare.berkeley.edu/alumni-action-mu-sochua-msw-81

Cowley, J. (2013, December 15). Dubbo Photo News. Retrieved from Cambodia: Country of Contrasts: https://www.dubbophotonews.com.au/news/general-news/top-stories/item/26…’

Karlins, A. (2015, December 15). Biography: Mu Sochua - Women’s Rights in Cambodia. Retrieved from The Heroine Collective: http://www.theheroinecollective.com/mu-sochua/

Khemara Cambodia. (n.d.). Khemara Cambodia About. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pg/khemaracambodia/about/?ref=page_internal

Robinson, A. (2018, September 13). A Trailblazer in Action: Mu Sochua’s Path into Cambodian Politics. Retrieved from Fair Anita: http://fairanita.com/blog/a-trailblazer-in-action-mu-sochuas-path-into-…

Sam, R. (2015). The Voice of One. In S. D. Party, Teacher Thinker Rebel Why: Portraits of Chee Soon Juan . Singapore Democratic Party.

Sochua, M. (2017, November 17). The demise of the opposition sounds the death knell for democracy in Cambodia. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/nov/17/opposition-d…