#FEMALEFORWARDINTERNATIONAL

A Woman on the Diplomatic Frontline

The legal expert paving the way for Ukrainian Human Rights legislation

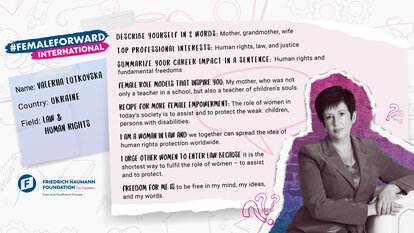

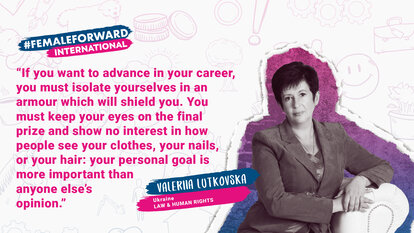

“It is not complicated for me to be a woman in my profession”, says Valeriia Lutkovska when asked what it is like to be the woman who negotiates the release of prisoners from occupied Crimea or fights for the improvement of conditions in the Ukrainian penitentiary system. “For me, it is about human rights – not empty words but standards in each sphere of our lives. And everyone knows who I am and that this is what I stand for. So no, I would not say it is hard for me. For women who want to work in the field of human rights, I have to say this: if you want to advance in your career, you must isolate yourselves in an armour which will shield you. You must keep your eyes on the final prize and show no interest in how people see your clothes, your nails, or your hair; your personal goal is more important than anyone else’s opinion.”

Lutkovska’s words are certainly a reflection of an ideal where a person establishes herself beyond gender. Her deliberate use of language reflects this too (Lutkovska has an excellent command of English, surely perfected during her long career as a diplomat); while Wikipedia still lists her as an Ombudsman, she calls herself an Ombudsperson. Her life and career make it clear that clichés and stereotypes do not apply. And she is clear about it in a diplomatic fashion – imposing the rules of our conversation without elaboration, firmly yet gently.

A stellar diplomatic career

Lutkovska raised her daughter with the help of her mother during Ukraine’s Democratic Transition while managing to finish two higher education curriculums: philology then law school. In 1999, she began her work with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). She was the head of the National Bureau for the Questions of the European Convention of Human Rights at the Ukrainian Justice Ministry. She affirms that her interest in human rights is long-standing and, that while in government, she helped prevent human rights abuses.

At the time, Ukraine lacked the special legislation needed to execute ECHR judgements, meaning that European law could not be used by Ukrainian national courts as a source of law. Valeriia Lutkovska decided that needed to change. Despite difficulties, eventually the two systems were successfully harmonized and today, numerous judges understand and use these laws in accordance with European jurisprudence.

In 2012, Lutkovska was elected the Ombudsperson of Ukraine for Human Rights, a position she held until 2018. She describes this time as the six most important years for both her career and for human rights in Ukraine. In 2013, the Maidan movement swept Ukraine after pro-European legislation was blocked due to pressure from Russia. Less than a year later, the Russian Federation annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, causing an international outcry and fuelling the ongoing war in this region and in Donbas. “It is very difficult to be the person who controls the application of constitutional laws in occupied zones”, she says.

Human rights in times of war

This war created a lot of victims, people internally displaced, tortured, or killed, Lutkovska says. She states that setting the international standards for the work of ombudspersons during wars was one of the most important issues in her career, as it should be for any ombudsperson. When she assumed her office, there were no international treaties regulating the functions of ombudspersons and decisions had to be made case by case. Lutkovska worked to create an international standard and a tool used by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), an organization that helps human rights institutions work with the United Nations. In 2018, GANHRI declared that it will make the standards developed by Lutkovska an international norm for the work of ombudspersons.

When the war in Crimea began, Ukraine lost a lot of people in its penitentiary system, since 30% of its prisons were now in territory it no longer controlled. This meant that more than 13,000 people were missing, Lutkovska explains. She started negotiations with the powers in the non-controlled territories to transfer these prisoners back to Ukraine. She regrets that not many were brought back, though a decent number – about 20 persons per month or 300 overall – were transferred due to her personal participation. She acted as a guarantor in the process, a neutral party between two adversaries, communicating with the authorities in both controlled and non-controlled territories. This was a strange, unconventional role for an Ombudsperson. She also documented systemic issues of how suspects were detained while their cases were investigated and contributed to the judicial understanding of the proper detention procedures in the Ukraine.

But for her, the most important cause during her ombudsperson work is the one Lutkovska calls “her lovely child” – the national Preventative Mechanism against torture. She set out to create this tool in May 2012, just a month after her election. It effectively opened the closed doors of the penitentiary system and the psychiatric hospitals, including institutions for children and the elderly. Her work on the Preventative Mechanism proved extremely important during the Maidan movement, when a lot of people were detained in abysmal conditions and Lutkovska and her team had the opportunity to enter the places of detention and appeal to Parliament about conditions there. She also worked on prison infrastructure, effectively closing an investigation centre in a 300-year-old building in Lviv. In another instance, she intervened and petitioned the Ministry of Health to improve conditions in a psychiatric hospital for felons.

When asked how she handles such heavy work, Lutkovska pauses only for a moment before answering: “While all questions concerning human rights were really interesting, it was only when I started my career as a government official that I truly understood human rights. While working with the ECHR, I saw that the Ukrainian state has many obligations that have never been clearly articulated. For example, the state must not only abstain from torturing people but also actively investigate when torture is committed. The state must not only prohibit, but also promptly investigate unlawful actions when they happen.”

Change comes from the individual

“It is also a question of my understanding of human rights, which revolves around dignity”, she continues. “Without an understanding of my rights as a human being, it is not possible to understand what human dignity is. Only the person who can protect the right of privacy, or education, or freedom of expression – only they can understand human dignity.”

For Lutkovska, it is important to educate Ukrainian society in those ideals. Ukraine is very paternalistic, she says. For example, even though there is a right to appeal to national courts to protect human rights, people prefer to write to the President, because they see him as a guarantor of their constitutional rights. This is a simplistic understanding: “Mr. President, please protect my right to an education.” But it does not work like that – one must appeal to the court for protection.

When she was an Ombudsperson, she received 20,000 letters per year. And it was terrible for her to read them and reply with the explanation that the person, first and foremost, must fight for their rights in court, prepare their case, and be ready to protect their rights. People would get mad, she says, and would say that she did not want to protect them. “But you must protect yourselves,” she says. This inspired her to work with Ukrainian civil society on educational initiatives which explain the procedures of fighting for one’s human rights.

It is a woman’s world

As an Ombudsperson, she joined a coalition of civic society organizations seeking the ratification of the Istanbul convention. A lot of women in Ukraine complain about domestic violence, and she took that problem to Parliament, urging MPs to ratify this convention and improve the situation. Not only women, she says, but also men complain about discriminatory practices, especially after divorces. She says that her country has an active organization of men who would like to live with their children and she admits that, as a woman, mother, and a lawyer, it puts her in a strange position but that she understands and sees the problem: when courts decide where a child resides, they defer to the Declaration of Children’s Rights, which states that after a divorce, a child should be with the mother, not the father. The problem was that this document was never ratified in Ukraine. Lutkovska resorted to the Supreme Court, asking judges not to use this provision because it is discriminatory. As far as the Istanbul convention was concerned, the Orthodox Church was against it – and no politician would go against the Church in Ukraine, she says.

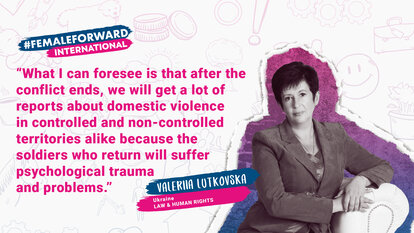

On the other hand, Ukraine established a special police unit, called POLINA, just to respond to domestic violence. Also, there is new legislation with special penalties for aggressors in domestic violence situations. Lutkovska says that this new law is good judicial text but not yet popular with judges. In her opinion, the issue is the cultural norm that internal family problems should remain in the house and not be publicly discussed. Domestic violence is not spoken about. The solution, in her opinion, is to work with the women and men concerned, explaining that the more open a society is about this issue, the better the State can protect people and defend human rights. “What I can foresee is that after the armed conflict ends, we will get a lot of reports about domestic violence in controlled and non-controlled territories alike because the soldiers who return will suffer from psychological trauma but seeking psychiatric and psychological help is not common in the Ukraine. The problems will remain in the family.”

The end of the conflict is Lutkovska’s priority now. Her country’s situation pains her: the internally displaced people, those killed in combat, and the soldiers still protecting the territorial integrity of her country. But she does not let this deter her. “It is hard for me, because I know we have good people in this country who do not want war but right now, there is no political will to stop it. And we have people in unlawful detention, we have people who have not received their pensions for the past seven years because we do not have the mechanisms to pay that money in the non-controlled territories: it is a case I have fought with the Social ministry many times. But I hope that someday, this war will be resolved in the interest of our society. And for me, as a lawyer, it is important to be ready for that time after the war.”

This is why in 2017, she began to prepare for “transitional justice”, a very specific area since while there are plenty of international standards, each country still has a specific approach to post-war justice.

What is her advice to people who wish to work for human rights? They must understand that it is a very difficult field, she says. “You will not be liked by the state and society, because human rights are about everyone, not just about the people who are in our party or those we agree with.” She tells the story of a case she recently started, representing the position of a toxic Ukrainian political party. She received a lot of criticism for her stance, but she fends it off: “The right of assembly – which this case is about – is a general right, not just for you or for people who share the same ideology as you. It is about all of us, and I will protect the right of assembly even if I disagree with the political position concerned. And this is one of many examples of the complexities of my field. You must be ready to defend human rights nevertheless.”

Lutkovska continues the fight for these ideals in her private practice, where she works side by side with her daughter. When her child was 16, Lutkovska asked her to visit the Law Academy in Kyiv to understand what an advocate does, and to see if she would like it. “Once I was free from civil service and had my own law firm, she came to work with me and it is great to have my daughter by my side as a professional,” she says. They worked an interesting case together recently, contesting the detention of a person who was accused of murder. They won that case. Her daughter also specializes in European law.

When asked whether she thinks she was the inspiration for her daughter’s career, Valeriia Lutkovska gives a shy smile and shrugs: “I hope so.”

There can hardly be any doubt.