France

A setback for Macron's electoral alliance? The French party system after the 2022 election cycle

French President Emmanuel Macron at a polling station in Le Touquet, northern France, on the occasion of the French parliamentary elections on 19 June 2022

© picture alliance / abaca | Pool/ABACALeft - Centre - Right, these are the coordinates of the political order in France since the French Revolution. At least this system of coordinates remained with the French voters after the second round of legislative elections this Sunday, 19 June, at the end of the 2022 election cycle. The new old President Emmanuel Macron and his main electoral opponents, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon have also remained the same since 2017. However, that was largely it for electoral continuities. What has changed with regard to the French political system?

No absolute majority for Macron - reorganisation in party competition

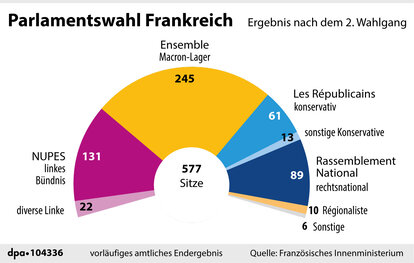

Particularly relevant for the future day-to-day government and completely unusual for recent French history is that the Macron alliance Ensemble was unable to win an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections and will now have to rely on permanent or occasional cooperation with other parties. In addition, with the cross-camp left-wing alliance Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale (NUPES) and the far-right Rassemblement National (RN), the radical representatives of the left and right camps are the actual election winners; the moderate representatives Parti Socialiste (PS) and Les Républicains (LR) have been marginalised parliamentarily, as the distribution of seats in the future parliament shows.

The fact that no party alliance was able to win an absolute majority is the direct consequence of the new tripartite division of the political system, where left, centre and right now face each other in parliament. Although France is not now facing cohabitation, i.e. the difficult cooperation of prime minister and president from different parties, dealing with the fact of not currently having a governing majority is also likely to lead to hectic talks in the coming days. After all, forming coalitions, which is the norm in Germany, is not part of the usual political procedure. It remains to be seen whether Ensemble will form a permanent alliance, i.e. a kind of coalition with the Republican Right of (LR), or seek majorities on a case-by-case basis.

In view of this "majorité introuvable" (undetectable majority), it is almost forgotten that the presidential elections and the period leading up to the parliamentary elections have already brought innovations: For example, that the presidential candidates of the hitherto dominant parties PS and LR each received less than five percent of the votes. It was also a first that apart from the re-elected representative of the liberal centre, Emmanuel Macron, with Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon as well as with Éric Zemmour, only representatives of the extremes received more than five per cent of the votes in the first round of the presidential elections. Overall, the result of a long-term process was evident here as well as in the parliamentary elections, which includes the loss of trust of the population in the established representatives of politics and the end of traditional party ties.

The new parliamentary arithmetic is also a consequence of the formation of the unexpected cross-party alliance NUPES in the left camp led by the radicals of La France Insoumise with PS, Parti communiste (PCF) and Greens (EELV). The alliance could - if it remains united and comes together as a parliamentary group - form the second largest group in parliament, but has little chance of structural participation in government.

Radicals have the advantage

The formation of NUPES in the dynamic of Mélenchon's strong result in the presidential elections and his resulting "candidacy" as prime minister have turned the previous power structure in the left camp upside down, but also the competition with the right. After all, NUPES succeeded in having the second largest group of MPs elected to parliament with 131 MPs; the Rassemblement National was able to increase its result more than tenfold compared to the previous legislative period and, with 89 MPs, reached parliamentary group strength for the first time; this is tantamount to an earthquake in the parliamentary life of the Vth Republic, in which the extreme right had hitherto had no significance. Assuming further unity in NUPES, both Les Républicains and the Rassemblement National have lost their roles as Macron's main challengers and are only the third and fourth largest groups in parliament. The formerly bipolar political system is thus for the time being divided into three, with the radicals on the left and the extremists on the right largely prevailing, while the centre is represented by Macron and his allies.

Setback for Renaissance

The further development of the En Marche! movement, founded by Emmanuel Macron in 2016, into "Renaissance" and its cooperation with other actors of the centre in the electoral alliance "Ensemble" can certainly be interpreted as a logical continuation of developments. The step corresponds to the usual processes of party development in France, where parties often rename themselves to symbolically herald new phases. The parliamentary elections have now shown how urgent this is: Although the current election cycle means another step for Renaissance towards establishing itself as a "normal" party, the result of the elections is more than sobering. Not only has it lost numerous constituencies to NUPES and RN, it is also more dependent on its alliance partners Mouvement Démocrate and Horizons. In addition, many familiar faces of the "Macronie", as Macron's party friends are called, were voted out of office, which is tantamount to a slap in the face for the previous government.

In the upcoming legislative period, Renaissance faces three important challenges: The party must emancipate itself bit by bit from its founder, improve local implementation and sharpen its thematic focus. Without Macron, a purely personalised election campaign like the one in 2022 seems hardly conceivable in the future regional, municipal and European elections as well as in the next presidential elections; moreover, the parliamentary elections have already shown that this is not (or no longer) a promising strategy. One way of doing this could be to play off the post-modern cleavage lines with which Renaissance or En Marche! has demarcated itself from the radical representatives of the left and right camps since its founding, while at the same time taking votes away from the moderates on the left and right. In view of the upcoming compromise-building within the framework of a coalition or of selective alliances, such a sharpening of content seems to be particularly difficult.

Another important challenge will be the reorganisation of personnel. After the foundation, personalities already emerged in the last legislative period who stood behind or next to the president in the public eye. However, with the now former parliamentary president Richard Ferrand and the parliamentary group leader Christophe Castaner, two of the best known among them were not re-elected. The most popular among them is the former prime minister Édouard Philippe, who in the meantime has founded his own party, Horizons, allied with Renaissance. To what extent this will compete with Renaissance in the future and whether Philippe could succeed Macron or compete with potential Renaissance candidates is still completely unclear. In any case, in view of the fact that it will not be constitutionally possible for Emmanuel Macron to be re-elected in 2027 and that some of its most important representatives have not been re-elected, Renaissance is urgently called upon to put (further) new personalities in the limelight who could then take over Macron's legacy.

New left front will oppose Macron's movement as opposition

The rapidly successful founding of NUPES under the leadership of Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the left camp was not expected before the parliamentary elections: Not only because Mélenchon had not been able to reach agreement on a joint presidential candidacy within the radical left just a few months earlier, but also because he succeeded in forming NUPES together with the moderates and Greens in the left camp. Whether this construction will be politically viable in practice and act as a united opposition faction, despite a significant parliamentary presence, is still completely open.

The Socialists, at any rate, have only achieved a halfway respectable parliamentary presence thanks to the alliance, and benefit from the fact that escape under the guise of a potentially non-permanent alliance offers them at least acute survival through parliamentary group size and party funding, and thus the chance for all-round renewal.

For no one in its ranks now denies that this is bitterly needed, especially for the PS; at most those who assume the demise of the party anyway. The PS has not been able to appeal to the traditional working class for years, it has lost its connection to them. Many of its voters have turned to the radical left or the extreme right Front National. The latter has recently been increasingly successful in appealing to members of the socially weak classes with its social populism. In addition, the PS has recently lost all confidence among left-liberal voters, some of whom voted for it at least until 2012. They have turned either to the radical alternative Mélenchon or to the liberal and pro-European Macron. For the population, the current political offer of the PS seems to have simply become superfluous; other, more innovative actors have stepped into the breach and apparently embody left-wing and/or social-liberal contents and values more credibly. Moreover, as new or opposition parties, they do not have the aura of being responsible for the economic and political crisis that has been felt for years and that has led to a loss of confidence among citizens in established parties, but also institutions and democracy itself.

Government pact or irrelevance of the Republicans

An all-round renewal also seems urgently needed in the traditional right in view of the defeat in the presidential elections and the result of the RN. After François Fillon failed to make it to the second round of the presidential elections in 2017, the party only grudgingly managed to unite behind the common candidate Valérie Pécresse in 2022, whose desolate result was to prove her critics right. The disputes over direction that have preoccupied the party since the end of Nicolas Sarkozy's presidency have already led to frequent expectations of a split and could now escalate in view of the question of a potential alliance with Macron. Given that the Republicans are an artificial construct of different party families, formed in 2002 under the impression of the strength of the then Front National, this is not very surprising. There seems to be hardly anything left of the traditional (neo-)Gaullist party, with members and party migrants flitting between cooperation with or even defection to Renaissance and sympathies with Éric Zemmour's Reconquête movement. Many liberal-conservatives have already turned their backs on the party in favour of the governing party, and individual prominent representatives are calling for cooperation with Ensemble in order to secure their own relevance; after all, there are quite a few former allies and party members in its ranks. If the Républicains were to become Macron's coalition partner and procure a majority, this would probably accelerate a possible split (which seems like a kind of irony of history, since until 2017 the centre parties were the potential procurers of majorities for the governing parties on the left and right). After the mixed results in the parliamentary elections, leading to a parliamentary group with 61 deputies, the question of the political future of the conservatives in France is once again raised.

On the way to the VI Republic?

Thus, the 2022 election cycle must be interpreted as a milestone in the transformation of the French political system. The provisional end of the bipolar order has prevented the structure-giving "fait majoritaire" (French technical term for the fact that governments are supported by stable parliamentary majorities), which until now could be considered a particularly trademark of the Vth Republic and brought with it a relatively high stability of governments. As a result, difficult government formation and changing majorities are to be expected. The hitherto structurally conservative electoral system has only retained its previous effect in a few places, where well-entrenched local heroes from the former governing parties could be re-elected. The "reversal of the electoral calendar" introduced a few years ago, whereby parliament is elected a few weeks after the presidents, has also not had the expected effect; the newly elected president was unable to secure an absolute majority. The new tripolarisation will change the rules of the game of politics in France, possibly even anticipating a constitutional change on the way to the VI Republic. It remains to be seen which of the political forces will be up to the task. All parties represented in parliament face major challenges, ranging from further establishment to preventing total irrelevance. Whoever succeeds best in overcoming these challenges is likely to have an important say in the 2027 elections.

Guest article by Dr. Daniela Kallinich.