European Elections

European Elections: More Drama than Change

A complex result

It seemed certainly like high drama: the French president, faced with a drubbing of his party at the hands of the far right Rassemblement Nationale led by Marine Le Pen, decided to dissolve parliament and hold new elections. In Germany, the ultra-right Alliance for Germany came second with 16% of the vote, while the ruling coalition lost heavily[1]. In Austria, the far-right Freedom party came first and doubled its seats in the European parliament. Headlines everywhere focussed on the surge of the far right.

However, despite these spectacular gains, the picture in other European countries was different. In Italy and the Netherlands, the far right more or less stagnated, with seats going from one far-right group to another. In Poland and Hungary, the Far Right also lost compared to previous elections. Ironically, the Far Right did better in the older democracies of Western Europe and failed in the newer democracies of Eastern Europe.

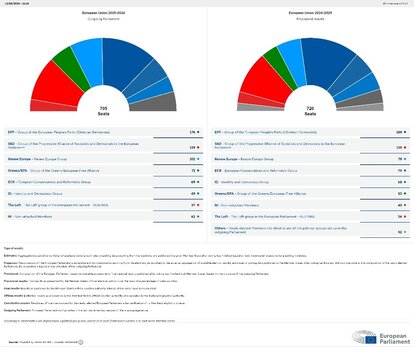

The overall result thus showed only a moderate gain of some 2.3% for the two Far Right groupings, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the Identity and Democracy (ID). The three largest groups remain, the European Christian Democrats with 26.3%, followed by the Socialists and Democrats with 18.8%, and the Liberals with 11%. These three groups have had an informal alliance since the founding of the parliament in 1979 in order to advance the pro European agenda, and they continue to hold a majority of seats even without the Greens who dropped from fourth to sixth place among the parliamentary groups[2].

The European elections must be understood as an addition of national results. Very few voters pay attention to parliamentary politics in Brussels, and the groups in the parliament are conformed by alliances of national parties. There are hardly any truly pan-European parties. The only notable exception is the left-liberal party Volt, which won 5 seats, 2 in the Netherlands and 3 in Germany, and may join the Liberals or the Greens.

This means that the European elections usually suffer from low voter turnout compared to national elections, and from a tendency of voters to cast a protest vote. Extremist, populist or satirical parties thus usually do quite well. This tendency explains the results in Germany and France where the governments were unpopular and people decided to vent, so they voted for extremists.

Common Political Issues

There are some common themes in practically all EU countries, such as immigration. Since 2015, the European Union has faced a growing wave of refugees, and the imperialist Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has increased the numbers even more. The commitment to humanitarian law that requires the European Union to shelter refugees clashes with a growing unwillingness in societies to tolerate such a high number of newcomers. Europe needs immigration, its population is aging and budgets everywhere groan under the burden of pension liabilities. However, integrating the refugees has not been easy, as countries have been slow to adapt their systems to help integrate them faster into society and the labour market.[3] Meanwhile they compete for cheap housing, another area where many European countries have implemented policies that have made housing more expensive and depressed construction of homes[4]. It is therefore not really surprising that the working class in Europe increasingly fears for its position and its future and turns away from traditional social democratic and socialist parties and moves to the far right – mirroring a trend visible among Trump voters.

The Far Right also does well in rural areas and smaller cities, as the big cities get ever more diverse, and the leftist-green lifestyle of well-educated urban voters exerts cultural dominance, clashing with more traditional rural lifestyles. Environmental policies to combat climate change have exacerbated this: while public transport in big cities enables people to live without cars, the same is not true for rural areas, and they resent the demonization of cars and ever-stricter environmental laws governing housing, heating, transport, or land use. These elections have, for the first time, brought a backlash against the Green agenda, with Green parties losing substantially, especially in Germany.

Extremists of the Right and, to a much lesser degree, on the Left, have also capitalized on people’s reluctance to support Ukraine in its fight for survival. This topic, however, has played a lesser role, and the relatively decent showing of Germany’s Free Democrats (5.2% compared to 5.4% in 2019) is largely due to its main candidate, the outspoken Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann, who has made a name for herself as a fierce supporter of Ukraine and a relentless critic of chancellor Scholz and his hesitant policies in support of Ukraine.

On the positive side, there is the lesson provided by the horrible experience that Britain had with Brexit: it turned out to be exactly the sort of economic disaster every economist predicted. This has forced the Far Right to rethink their position on the EU, and calls for exits of France (Frexit) or Germany (Dexit) have quieted down. The Russian attack on Ukraine has also reinforced the view that Europe does need to stick together to survive and thrive in difficult times. There is, in sum, still a lot of life left in the European project.

What does this mean for the rest of the World and especially Latin America?

All in all, the democratic centre in Europe has held firm, but it is weakened, and the slow advance of extremist parties continues. This is not happening in a vacuum - there are credible reports about covert infiltration and payments from Russia and China to parties of the Far Right[5]. The elections have thus been a battleground in the undeclared war that authoritarian regimes, especially Russia, are waging on liberal democracies.

Looking forward, the impact on Europe’s external relations, including with Latin America, might be subtle but significant. While the pro-European center remains dominant, the growing influence of populist and extremist parties could steer policies towards greater protectionism, potentially stalling trade agreements like the aforementioned ones with Mercosur and Mexico. Nonetheless, the European Parliament is expected to maintain its stance on democratic values and continue addressing global issues, including human rights abuses by authoritarian regimes. The resilience of the European project, despite internal and external challenges, remains a testament to the enduring appeal of European integration and cooperation, for now.

[1] Comparative tool | 2024 European election results | European Parliament (europa.eu)

[2] 2024 Election results | 2024 European election results | European Parliament (europa.eu)

[3] European countries should make it easier for refugees to work (economist.com)

[4] The growing global movement to restrain house prices (economist.com)

[5] Espionage scandals are hurting Germany’s far right (economist.com)