Lashes and Suffocation Take Turns

Throughout 2016 and 2017, the decline of the freedom of media, expression and opinion continued. As Freedom House (FH) has recently noted in its report “Freedom of the Press 2017”, it is a world-wide trend, which to a considerable degree also took its toll on the most press-friendly countries such as the United States of America, let alone on those that have always been troublesome in the field. Sad examples of steep decline in media freedom outnumber the bright examples of improvement.

Same situation occurs in South Eastern and Eastern Europe countries. Over there, all those is even more worrisome, in that some of them are European Union members, candidates or aspirants, while the rest are its neighbours. Crimea, a Ukrainian territory annexed by Russia in 2014, has been ranked – by the FH – as one of the ten worst territories in the world regarding media freedom (consequently also regarding freedom of expression). An EU-member Hungary, as well as EU-candidates Turkey and Serbia, have suffered the worst setbacks. In majority of other Balkan countries, the situation is slowly regressing. In the region, improvements were notable only in Greece (to it, a considerable one) and in Belarus (in its case, alas, from a very low previous position).

Protests against closing down independent media in Turkey.

Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF) has also been monitoring press freedom, in the framework of its project- the comparative index- Freedom Barometer. It was launched in 2013 in order to monitor, evaluate and comment on the state of freedom in five Western Balkan countries. It was later gradually extended to 30 countries of Europe and Central Asia, while currently encompassing 45 countries, with the ultimate goal of covering entire Europe and Eurasia. The methodology of the Freedom Barometer stipulates freedom of media as an important part of political freedom, which to its part, together with economic freedom and rule of law (as seen through independence of judiciary, lack of corruption and a respect for human rights), is a pillar of freedom as understood from a liberal perspective.

The importance of press (or other media) freedom does not disappear outside the purely political sphere (i.e. as a catalyst of free and informed electoral choices, or an obstacle to unconstitutional vetoing in politics, or an element of checks and balances in modern democratic society). Free media are also crucial for fighting corruption, for protection of human rights (e.g. freedom of expression, opinion, research, etc.) and public exposure of human rights abuses, or even for achieving more economic freedom (thus a more prosperous economy). At the same time, independence of media sphere is a thorn in the heel of all those politicians with autocratic tendencies (and such are amassing as the technical means for manipulation develop as fast as the means of information exchange), or of other corrupt elites.

Countries of Eastern and South Eastern Europe have all experienced various authoritarian (or even totalitarian) regimes in the second half of 20th century. Along the process of transition into pluralist democracy their elites and population understood the importance of media freedom for free society. Along the EU-accession process, the EU has been encouraging and assisting them in developing a free media sphere as part of an autonomous civil society.

Meeting of investigative journalists from Moldova

Yet during the last decade many of those accomplishments have been imperilled. Democracy as such in some of those countries is in retreat. Either authoritarianism, or populism, or both, took charge. New autocrats, themselves often freely elected, set as their first priority solidification of power through limiting the independence of judiciary and stronger control over media. Pressure on independent media often goes hand in hand with a take on other civil society organizations.

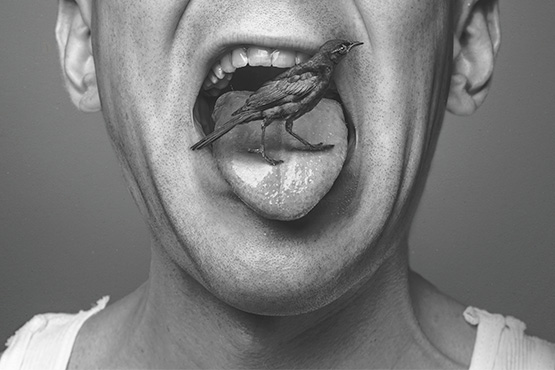

In the mentioned countries, one cannot find as cruel treatment of media and journalists as in some other parts of the world. There is no public lashing, death sentences, even no outright censorship. Assassinations of journalists are relatively rare, yet even those are a serious threat for others and an attack on free speech, since perpetrators either remain undiscovered or the trials against them become farce. The political background of those crimes is never revealed.

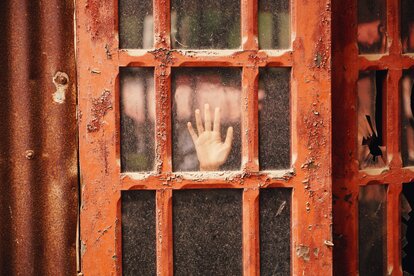

Russia and Turkey lead the way in creating a system unfriendly towards media freedom. In Russia, almost all the loopholes through which a free word could pass through are already closed and online media are the only one still struggling to maintain some degree of independence from the authorities. In Turkey, where the process had started later, but has intensified after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, closing down media houses and arrest of hundreds of journalists are commonplace. Censorship on the Internet is getting ever stronger. Vilification of dissenting journalists (or other potentially non-likeminded public figures) by the highest ranking politicians is also becoming a norm.

BIRN Albania journalist, Lindita Cela, received an international award for investigative journalism

In the post-communist countries of South Eastern Europe, who without exception long for EU membership, the methods of silencing the non-compliant media are more sophisticated than in those regimes which openly refuse (or are expectedly going to be refused) an EU future. “Lashing” media via outright bans, closing them down, legally stipulated censorship, or sending journalists to serve prison terms for what they said or written, are unusual. Instead, lashing of non-compliant media is mainly verbal. But it is constant and it is sometimes harsh indeed.

The examples of Serbia and Macedonia (the latter prior to the changes in late-2016 and spring 2017) are paradigmatic. State presidents, PMs, government members or other highest officials used almost every contact with non-likeminded media to mention their ownership structure (either partially foreign, or with ties to business sector or equally vilified NGOs or opposition political parties), their alleged bias towards the government, or a lack of ethics as something that readers and viewers should take into consideration. Such disclaimers are often in a form of disqualification or open denigration. They are de facto a call to the public to dismiss the information obtained through those media as irrelevant at best while malevolent at worst.

As for ownership structure and its transparency, governments should be blamed more than private media. Privatization of media is an unfinished task, while it, even where completed, played into the hands of corrupt or other crony, pro-government owners. Attempts are enduring to reverse the previous transformation of state-owned broadcasters into public broadcasting services and to re-etat them (Poland is a vivid example, even though more subtle attempts – such as via financing - are on the way in almost all the countries of the region). In Romania, the government intervened against a suspected corruption by public broadcasting authorities themselves. In a few other countries it also could have done the same but it did not.

Even when private, when free of direct attacks and when willing to play the role of the correctional factor of government, media face another threat – financial suffocation. It might be through libel lawsuits which are decided by courts in a few months’ time when it suits pro-government media or the government, while dragged on for years when the charges are put by a non- or anti-government organization or individual. Pro-government media enjoy a relaxed attitude by tax authorities – they are tolerated even when they delay the payments for years, or when they employ people on an informal basis, while non-compliant media are regularly or even excessively visited (and fined) by auditors and various other inspections. State subsidies to media, which are legally allowed on the “project” basis, often become just another form of permanent support, selectively given to media that favour ruling political parties or at least abstain from criticism of the government. At least at the local level, such financing might be considered as a form of illicit financing of political parties and/or activities. Access to information, or even physical access to government premises as the site of reports, is in some countries a matter of favour, granted to government friendly journalists or media.

Local newspaper owner/editor from Serbia, Vukašin Obradović, on hunger strike against suffocation of independent media.

Therefore, even when and where a fair competition between media for the public is the officially proclaimed policy, the playing field is not level at all. Since private-owned media depend on advertising that is another field where their access to customers and partners is hindered if they are hostile against the government.

Namely, the economies of South Eastern Europe (especially in ex-Yugoslavia) are still statist. The share of the public spending in GDP is near or even is surpassing one half. With huge proportion of public procurement, corrupted tender procedures, partitocracy in public sector companies, etc., most of the economy is in one way or another dependent on the government (at the local level even more than at the central). It is no wonder, thus, that a media house which turns against the government (or is labelled as such) suddenly and without any explanation (or marketing analysis) loses many of its sponsors, i.e. companies that used it for advertising. Marketing, advertising and PR companies are anyway too few. Their main customer is the public sector, thus making them another factor of pressure against the independence of media.

Likewise, improvements in the field of economic freedom, such as those in Greece, following its agreement with international creditors as of summer 2015, especially the de-monopolization of some sectors of real economy, coincided with improvements in the freedom of media. The causal connection between those two seems likely, albeit too early to be claimed.

With freedom of media endangered, other freedoms also come into question, or become irrelevant, such as freedom of opinion and expression, and to a degree also freedom of art and scientific research. Especially in social science, such as history (but sometimes - as in the case of a scientific debate in Serbia over long-term effects of NATO intervention on public health - even in natural science), hidden censorship by the government or by pro-government pressure groups, or self-censorship by media (in constant fear of being labelled as non-patriotic), are keeping the facts or views that run contrary to the official narrative away from public eyes.

The latest Freedom Barometer research, encompassing the period between mid-2016 and mid-2017, the results of which would be published this autumn in the Freedom Barometer Europe Edition 2017, showed stagnation - as compared with Europe Edition 2016 - in Ukraine (which has obviously lost its post-2014 democratization momentum while remaining rather an un-free than a free environment for media), Russia (itself at a very low score 1.70/10.00), Moldova, Romania, Albania and Slovenia (itself by far the best among countries dealt with in this article, with the score 7.70/10.00).

Some countries have advanced: Greece (from 5.20 to 5.60, out of 10.00 possible positive points), Croatia (from 5.80 to 5.90) and Belarus (which is not encompassed by Freedom Barometer yet, but if it were, it would be marked 1.70, as compared to the previous year`s 0.90). But, a number of countries scored down: Turkey (by -0.50), Hungary (-0.40), Serbia (-0.40), Montenegro (-0.30), Macedonia (-0.20, whereby would-be results of a brand new government are too early to be evaluated), Bulgaria (-0.20), Bosnia and Herzegovina (-0.10) and Croatia (-0.10). In the narrative section of the coming Freedom Barometer edition, all those and other figures will be more thoroughly explained.

To conclude, freedom of the press or other media, of expression and of opinion is in decline and under grave threats in much of South Eastern and Eastern Europe. FNF will therefore continue paying special attention to it in its Freedom Barometer and other projects.