Democracy Backslides in Philippine Elections

The midterm Philippine election in May is a turn for the worse in a fragile democracy. It is further hurting political parties, already one of the weakest institutions in the country, and giving greater boost to personality politics. It is also taking place amid a climate of fear.

At stake are 12 of the 24 Senate seats, the 297-member House of Representatives, and thousands of local positions across the country: provincial governor, vice governor, and board members; city and municipal mayor, vice mayor, and councilors.

As events unfold, we are seeing President Rodrigo Duterte leave his mark on the upcoming elections in ways that are corroding the most visible practice of popular participation. Four developments are happening for the first time, differentiating the 2019 elections from past ones.

Consider these:

- The President is not endorsing a full slate for the Senate from his political party and is instead pushing for personalities loyal to him.

- The ruling coalition is fielding 13 candidates for 12 Senate seats to accommodate allies.

- Rival candidates in some local contests are endorsed by the President, sowing confusion and blurring political party lines.

- The President is heavily influencing local races through fear and intimidation, publicly naming candidates who are supposedly involved in drug trafficking although no cases have been filed against them.

Deviation from past

In the past, presidents campaigned full throttle for a complete senatorial slate. President Benigno Aquino III, in 2013, had his Team PNoy, grandly presenting the coalition of candidates from various political parties, in a historic venue, the Club Filipino. It was where his mother, Corazon Aquino, took her oath as president as the dictator Ferdinand Marcos was deposed. Nine of the 12 Team PNoy candidates won.

TEAM Unity was President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s alliance in 2007. She cobbled her team from various parties, presenting a united ticket, but only two of her candidates won, reflecting her sagging popularity.

Before that, in 2001, Arroyo campaigned for the People Power Coalition of which eight candidates won; four from the opposition completed the 12 Senate seats. Joseph Estrada was forced to resign as president in early 2001 after corruption scandals triggered a “people power” revolt. Arroyo, who was vice-president, took over, blessed by a Supreme Court ruling.

In 1995, President Fidel Ramos put together the Lakas-Laban Coalition composed of the two biggest political parties at the time, Lakas-NUCD (National Union of Christian Democrats) and the Laban ng Demokratikong Pilipino (LDP). Most of the Coalition’s candidates—9 out of 12—won the Senate elections.

The 1987 senatorial elections did not happen during the midterm as it was part of the transition to democracy after the popular revolt that kicked out Marcos in 1986. President Corazon Aquino’s 24 candidates ran under the Lakas ng Bayan Coalition or LABAN and 22 were swept into victory by her overwhelming popularity.

In these past senatorial elections, except for one, most of the administration candidates won the race. This is expected as well in May as Duterte continues to maintain majority approval. As of April 2019, the President enjoyed a 66% satisfaction rating, which is “very good,” rising from 54% in September 2018.

In this crowded race, where 62 are aspiring for the 12 Senate seats, the ruling coalition is likely to win at least eight seats. Incumbent senators who are running as independent and come from other parties can win at least two, while the opposition can get two seats at the most—or none at all, as a recent survey shows only one opposition candidate hanging on to the 12th slot. The winners will serve for a term of six years.

While past presidents saw to it that they carried a full slate, Duterte, together with his daughter, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, don’t mind putting more than the required number of candidates in their tickets. The President’s party, PDP-Laban, has allied itself with Sara’s newly created Mindanao-based party, the Hugpong ng Pagbabago (Faction for Change).

Their coalition of parties cements the alliance of Duterte, and the forces of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and the Marcoses, led by the children Imee and Bongbong. The main criterion for choosing these candidates was their support for the Duterte administration and their chances of winning.

Sara explained the seemingly illogical move of pushing for more candidates than the 12 Senate seats, saying that 13 aspirants approached her party and that she had no choice but to help them in the campaign: “We are giving people the choice, the individual voters, the 12 they will pick out of the 13 candidates that Hugpong ng Pagbabago is supporting.”

Julio Teehankee, an academic who has extensively studied Philippine political parties, sees this as simply the “politics of accommodation.” As the old adage goes, politics is addition.

This practice, while new in the national scene, has been going on in Davao. During elections, then Mayor Duterte endorsed competing candidates for city council seats. “It’s self-serving,” opposition Senator Francis Pangilinan, told me in an interview. “Those whom Duterte endorsed, no matter that they belonged to rival camps, campaigned for him.” In the end, it benefited him, even if it meant that political party lines vanished.

Duterte is deviating from the post-Marcos senatorial elections by favoring three candidates loyal to him: his aide, Christopher “Bong” Go; former Philippine National Police chief Ronald “Bato” de la Rosa; and his political adviser, Francis Tolentino. Of the three, he has campaigned most visibly for Go, as seen in tarpaulins, posters, stickers, and ads, their photos side by side.

Winning formula: Go

The 2019 senatorial elections are confirming formulas by which candidates can win. Three routes illustrate the ways by which Philippine elections can be won: through the power of a popular president; the allure of show business; and the endurance of political brands.

The most striking case is that of Go who has zoomed like a meteor, coming from nowhere and baffling many with his sudden and swift rise. He has never served in public office, a virtual unknown until Duterte became President. Go, his ever-present sidekick since his years as mayor, was the bearer of Duterte’s mobile phones, making him the favored gatekeeper and whisperer. He became known for taking selfies with Duterte, from the private confines of the President’s Davao home, to world leaders’ meetings in various global capitals—all of these photos exhibited in his social media accounts.

Beyond this, official papers for the President’s review and signature are funneled through Go. Imagine the pile of documents passing through him, clogging in the process, like a pyramid. This has given him tremendous power, flowing from his proximity and access to the President.

When he showed his intent to run for the Senate in 2018, he ranked low in the polls, way behind the top 12. The number of Filipinos who said they would vote for him was a meager 5.9% in March 2018. But almost a year later, this ascended to 53% in February 2019, landing him in the third highest slot. Pulse Asia research director Ana Tabunda was quoted in Rappler as describing Go’s rise as “spectacular…[and] unique.”

What does this say of Philippine politics? It is an example of how to make something out of nothing—courtesy of factors such as the President’s endorsing power and popularity, the candidate’s seemingly unlimited coffers, and the use of government resources and machinery.

Oiling the government machinery during elections is not new but it has been very visible in the case of Go. Local government officials have been reported as prominently displaying Go’s tarpaulins and posters, a common occurrence in various cities and towns. In an event organized by the Department of Interior and Local Government, Go’s campaign t-shirts were distributed, reaching captive audiences.

Moreover, the state-funded Philippine News Agency has frequently reported on Go’s activities during the campaign despite his resignation from government. The Philippine Information Agency assists Go during his campaign, at times sending local reporters to cover him, even feeding them with questions.

Money doesn’t appear to be an issue. The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) tracked how much senatorial candidates have spent for their ads for about a year, from January 2018 to February 2019, and found that Go forked out the most: P422 million. But his net worth as of 2017, as filed in his assets statement, was only P12.85 million.

The show business route

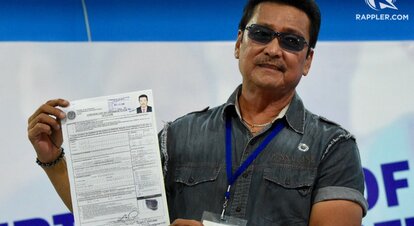

Another candidate of the ruling coalition, a former senator and movie actor with a moribund career, has successfully made a comeback through primetime TV: as one of the main characters in a top-rating telenovela aired on the giant network ABS-CBN. Lito Lapid served as senator for two consecutive terms, from 2004 to 2010 and from 2010 to 2016, and has since been gone from politics. His stint in the Senate is remembered for his silence on contentious legal and political issues.

Yet he is making a remarkable return: Lapid has been in the top 12 senatorial choices of national surveys and has a chance of making it back to the Senate. Ronald Holmes, Pulse Asia president, was quoted by the online news of ABS-CBN as saying: "If it’s top-rating, then that’s free media mileage…" The telenovela has been a long-running action drama series and has given Lapid tremendous boost.

Forgotten is the cash-smuggling case against his wife, Marissa Lapid, who was charged in U.S. courts for not declaring $40,000 when she flew into Nevada in 2010. (Her husband was senator at the time.) She was arrested and has since served her 3-year probation sentence. The U.S. government also forfeited about $150,000 in funds deposited to various bank accounts in the U.S. Marissa had a residence in Las Vegas and was a permanent resident at the time.

Joining Lapid in this celebrity category are movie actors and former senators Bong Revilla and Jinggoy Estrada. Surveys show Revilla remains popular, making it to the top 12 while Estrada is on the edges, trying to get in. Both have been charged with plunder for allegedly lining their pockets with public funds and have served time in prison. They have been released: the courts have acquitted Revilla while Estrada is undergoing trial.

Grace Poe, adopted daughter of a famous movie actor who ran for president but lost, capitalized on her ties to show business when she ran for Senate the first time. She currently leads the surveys in her re-election bid, keeping the glitter of the Poe heritage.

Political brands

Those who do not have the abundant largesse of Go and the telenovela exposure of Lapid rely on their own political brands to whisk them over to the Senate. These means building their names in politics, not just by themselves, but by family members who have been ahead of them in national races. Direct links to dynasties matter especially in a country where name recall is paramount.

These candidates include the likes of Nancy Binay, who is running under her own party, Mar Roxas and Bam Aquino of the opposition Liberal Party, and ruling coalition members Cynthia Villar, Pia Cayetano, Sonny Angara, Imee Marcos and Koko Pimentel. Their surnames have been etched in Philippine politics, both local and national, for decades.

- Nancy’s father was Makati mayor and later vice-president.

- Mar’s father was senator in the 1960s but the Roxas surname was carried on by his sons in Congress and in the Senate where Mar served. He was also in the Cabinet of two presidents.

- Bam, first cousin of former President Benigno Aquino III and nephew of former President Corazon Aquino, comes with a minted surname.

- Cynthia’s husband is a former senator and congressman while she, herself, was in Congress for three terms.

- Pia belongs to a family of politicians, starting with her late father, who was in the Senate, and her brother, who was congressman and also senator. She herself served in Congress and is also a former senator.

- The late Edgardo Angara, father of Sonny, was in the Senate for three terms and served in the Cabinet as well.

- Imee is the daughter of the late President Ferdinand Marcos whose family members continued their interrupted stay in politics upon their return from exile.

- Koko, for his part, is the son of former Senator Aquilino Pimentel who has been in politics for decades.

Resources, of course, matter. Campaign strategists say that P100 million (about $2 million) is adequate although this is a bare-bones budget. Television ads, which reach most of the voters, are expensive and going around the country entails huge costs. This is why candidates raise funds mostly from big businesses which happen to have vested interests. They, in turn, are able to push their own agendas when the candidates they funded win.

The new Senate that will convene in July will continue to have the opposition in the minority. This does not mean, however, that all of the senators belonging to the administration coalition will necessarily stand by Duterte on all issues. Since they were voted for their personalities rather than platforms and since they are politicians attuned to the public pulse, they will vote for legislation guided by their interests, especially those who plan to run for president in 2022. As of the latest survey, two to three candidates of the ruling coalition are seen as diehard loyalists of Duterte.

Local contests

In the local races, the Lower House polls are shaped by town and city dynamics and issues. As in past Congresses, winners in the House of Representatives ally themselves with the administration because cooperation improves their access to funds.

But there’s one thing different in the 2019 elections: President Duterte’s anti-drug agenda is shaping some of the races. “You have a former mayor who is now President, and he is bringing to a national scale the local campaign tactics of black propaganda and demonizing one’s enemies,” Miriam Grace Go, news editor of Rappler, and an expert on local governments, observed. This was highlighted when Duterte released a list of local politicians supposedly aiding drug dealers or are in the business themselves.

Rappler’s Go pointed out that it used to be that local candidates would only expect negative campaigning by their rivals, but now black propaganda can even come from the President: “Before, the allegations made by competing candidates were of immorality and graft; now, it’s about drug links – a charge that implies the candidates have destroyed lives, families, and communities.”

She explained: “Given the pattern that we’ve seen—of local officials getting killed weeks or months after being cited in the drug list or cursed by the President in his speeches – [we can say] if the President doesn’t like you, it’s like the death sentence to your candidacy.”

An opposition senatorial candidate, Gary Alejano, said Duterte is trying to control the local elections: “The public-shaming that the government is resorting to is aimed to intimidate and control the local politicians in the coming elections.”

As Rappler wrote in its editorial:

We have not seen anything like this since the fall of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986: a strongman inserting himself in local elections by carpet-bombing his enemies. He intends to take votes away from them through means and resources available only to a President.

Issues, styles

Unfortunately, in the national campaign, issues do not make or break candidacies. The ruling coalition candidates as well as those leading in the surveys have avoided televised debates and forums to stay safe, stay away from controversies, and protect their numbers.

Still, one issue that unavoidably surfaced in the national campaign is China: its aggressive actions in the West Philippine Sea (mainly limiting fishermen’s access and swarming Pag-asa with Chinese militia vessels), infrastructure contracts that are detrimental to Philippine interests, and the entry of thousands of Chinese workers into the country which cause resentment among Filipinos complaining of a tight job market.

Opposition candidates have hammered Duterte on his policy of appeasing China while the President lashed back at them while spreading fear that a war between China and the Philippines will take place should he stand up to his favorite ally.

More often, he insults them, bringing the campaign to a low. Here are a couple of examples of Duterte’s rants, as reported by Rappler reporter Camille Elemia, who covers the campaign of the ruling coalition:

This Chel Diokno, is he a girl or a guy? He's the dean of the College of Law in La Salle. That's why that son of a bitch school does not top the bar exams until now. What did he do? Nothing. He keeps on criticizing me but he himself is not good… He has big gums and a face. He is ugly.

When we [Duterte and Roxas] had the debate, I was really discourteous. I have no respect for him. He has no principles. He kept on going in and out of the toilet. I told him: "Mar, you seem nervous. It's your 10th time to go in there. All the urine in the toilet, it's all yours.”

Overall, Elemia wrote that the “8- to 10-hour gatherings filled with song and dance numbers, insults against critics, and late night rants led by President Rodrigo Duterte define most PDP-Laban campaign rallies.”

The campaign styles of the two camps are a study in contrast. Rappler’s Mara Cepeda, who follows the opposition—they have called their team Otso Diretso (Straight Eight)—wrote that the sorties are usually dialogues with residents of towns and communities where local issues are taken up. Attendance is small.

In one instance, “there was no stage, no tents, no complete sound system. Instead, the opposition senatorial slate’s campaign team picked a spot on the street in front of a basketball court, plastered the candidates’ posters on a wall, then lined up monobloc chairs on the sidewalk for the Otso Diretso bets to sit on,” Cepeda wrote.

The 2019 campaign has been tough for the opposition. For one, Pangilinan told me, it’s been very difficult to get local politicians to endorse Otso Diretso for fear of losing access to the President. Funds from businesses have been scarce also because of fear of Duterte’s wrath as well as the poor showing of the candidates in the surveys.

Facing these constraints, Pangilinan, the campaign manager, and the candidates rely heavily on volunteers to campaign, mobilize voters, and watch the count during election day. The 2019 elections will be a novel experience in this sense because local officials and members of political parties, veterans in organizing for elections, usually handle these tasks.

The opposition is fielding only eight candidates because it is fragmented, lacks resources, and it is up against a powerful enemy. The challenge for them, in this uphill battle, is to get five candidates in to add to the three incumbent minority senators (Pangilinan, Franklin Drilon, and Risa Hontiveros). There would have been four opposition senators but one is in prison, Senator Leila de Lima, who was sent to jail by Duterte on trumped-up drug charges.

What does it mean to have eight opposition senators in the 24-member Senate? This number could make the opposition effective primarily in thwarting attempts by the administration to slide the country into autocracy through legislation. But getting five candidates in is a dream.

There is an election, however, to look forward to—in 2022—when the country will vote for a new president. It is something both camps are preparing for, with the midterm polls as a precursor.