Economy

The Economic Fallout of COVID-19 in the Philippines

As of April 7 the Philippines has the second-highest number of COVID-19 cases in ASEAN, next to Malaysia.

The number of cumulative cases has been rising exponentially for some time, and notwithstanding testing delays experts believe the epidemic curve hasn’t peaked yet.

President Rodrigo Duterte responded to the epidemic chiefly by imposing a partial lockdown of Metro Manila on March 15, followed by a lockdown of the entire Luzon Island on March 17.

As in many other countries, the pandemic has upended the Philippines’ economic landscape. But it has been worsened by glaring gaps in social protection and governance.

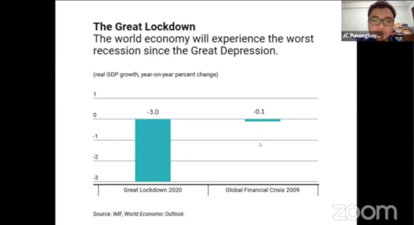

Macro impact

Metro Manila constitutes more than a third of the nation’s output in terms of GDP, while Luzon Island accounts for nearly three-fourths. With these areas under lockdown, the Philippines is bracing for a severe economic downturn.

The country’s planning ministry forecasts that GDP growth could drop from 5.9% in 2019 to 4.3% this year at best, –0.6% at worst. These figures still exclude the potential effects of the Luzon lockdown. Hence, the country could soon suffer its first recession since the Asian financial crisis.

The Asian Development Bank published a report showing how different sectors are likely to be hit. Under various assumptions, business, trade, personal, and public services are to be hit the most. These are followed by manufacturing, utilities and construction; hotel, restaurant, and related services; agriculture, mining, and quarrying; and finally transportation services.

Total economic losses could amount to $2.6b with a shorter containment, $5.4b with a longer containment. But these estimates could nearly triple or quadruple, respectively, in the event of a more significant outbreak.

China, the origin of the coronavirus, was the Philippines’ top trading partner in 2019. Weak demand from China is likely to hurt the most Philippine exports of electronic data processing, bananas, copper, and travel goods.

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs)—which constitute nearly all formal business establishments in the Philippines—are also under threat. Some are already beginning to fold due to low aggregate demand, choked supply lines, and lacking government support. Unfortunately, the finance minister said financial assistance for firms will have to “take a back seat” for now.

Social protection gaps

The fallout of COVID-19 in the Philippines has been worsened by glaring gaps in the country’s social protection system.

Duterte signed into law on March 25 the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act which authorizes him to generate savings from the existing budget to help finance efforts against the epidemic.

The law also provides for a monthly emergency subsidy of P5,000 to P8,000 per Filipino household, to be given to 18m households nationwide in April and May.

The problem is that there is no readily available infrastructure to deliver cash aid to this many households. Absent clear guidelines from the national government, local government units are forced to improvise and devise their own targeting schemes, leading to confusion and accusations of patronage among their constituents.

To expedite aid, some argue that it may be time to push for temporary universal basic income. But as it is the government finds itself cash-strapped.

Apart from the monthly emergency subsidy, the Bayanihan law did not detail a budget for economic relief for other sectors, notably MSMEs. Congress has yet to pass a separate, comprehensive economic rescue package.

Governance gaps

The country’s response to COVID-19 has also been derailed by a series of governance lapses.

The first confirmed case in the Philippines—a Chinese woman who flew in from Wuhan—was announced as early as January 30. But the health minister was reluctant to impose any sort of travel ban from China, warning lawmakers of “possible repercussions” and saying China “might question why we’re not doing the same for all the other countries that have reported confirmed cases.”

On Valentine’s Day, in a bid to show everything was fine, Duterte even invited Filipinos to “travel with [him] around the Philippines.”

In early March Duterte finally declared a state of public health emergency. But not long after the health minister admitted he himself should have declared it sooner.

Duterte put Metro Manila under lockdown on March 15, but it was criticized for focusing too heavily on police and military operations rather than on the need for widespread testing and the plight of health frontliners, who urgently need personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. On April 1, Duterte even ordered the police and military to “shoot” down anyone who causes “trouble.”

Duterte also pushed for emergency powers that would have given him, among others, the ability to take over private establishments. The final Bayanihan law omitted such powers, but ended up penalizing purveyors of “fake information” even without defining exactly what exactly it entails (legal experts say this is unconstitutional).

The pandemic requires heavy-handed government intervention, but all over the world authoritarian leaders have seen it as an opportunity to consolidate power. There are fears Duterte might be going the same path.

Two crises

On April 7, the Luzon-wide lockdown was extended until April 30.

Some experts claim this is necessary to quell the epidemic. But others say this might be unsustainable: absent sufficient help from government millions more Filipinos will be buried in poverty, and thousands could die of hunger. Indeed, many poor Filipinos fear hunger far more than the coronavirus.

In any case, the government must step up its social protection measures and get its act together. It’s bad enough for Filipinos to suffer the worst public health crisis in decades, but worse to have a governance crisis accompany it.

The author is a PhD candidate at the University of the Philippines School of Economics and a columnist of Rappler.com. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.