South Sudan Elections Come with a Big Question Mark

A Brief Overview of the Crisis

South Sudan, the youngest country in Africa, is listed amongst the twenty countries with the most challenging elections that Africa is going to witness in 2018. The reason why holding its first ever elections comes across as a challenge are multifarious but can largely be attributed to one factor, that is the country is at war. South Sudan has been war torn for 5 out of 7 years of its existence, not to forget the three decade long Sudan Civil War its people fought prior to that.

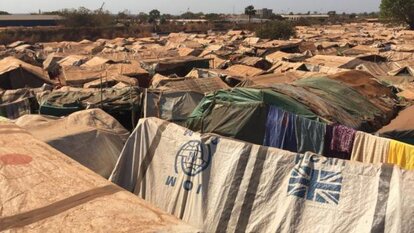

Known as one of Africa’s greatest tragedies, South Sudan today is in dire humanitarian crisis. It is bereft of peace, prosperity, economic stability, political legitimacy, legal administration, freedom of thought and expression and of course, human rights. Since 2013, 4.5 million people have been driven from their homes- the same number of Southern Sudanese displaced during the entire Sudan civil war. The number of refugees fleeing from South Sudan to Uganda alone crossed the one million mark in 2017. This manmade crisis is escalating in tandem with increases in violence. Amidst all of this, South Sudan's President Salva Kiir has started lobbying for elections to be held on the 9th of July 2018 despite such unfavourable conditions.

President Kiir is said to fear the loss of his legitimacy and the creation of what he calls “a political vacuum” after the term of the transitional government, signed by him and rebel leader Riek Machar, expired in February 2018. As per the August 2015 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which laid the foundation of the Transitional Government of National Unity, elections were to be held within 30 months to maintain validity. In spite of momentary respite after the peace agreement, South Sudan sprang back to conflict due to ceaseless rebel infighting and has never resorted to democratic means for a solution.

Mediations from the International Community have not resulted in a tangible breakthrough. Reasons for this included disagreement on power sharing among the diverse groups and a lack of positive engagement from the two rebel leaders. The latest development being that, after nearly two years since their last meeting, rival leaders President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar met face to face on 20 June in Addis Ababa to start a new round of talks to end South Sudan’s prolonged civil war. They later agreed to a permanent ceasefire to take effect within 72-hours on 27 June in Khartoum but the ceasefire agreement was violated within hours after it was signed. President Kiir also presented plans to extend his term for another three years in parliament on Monday 2 July, a move that was rejected by the opposition but will be voted on in parliament later in July.

As successful peace talks seem unlikely to occur, some are calling on the international community to take a tougher stance to stop the conflict. Former United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, called for harsher sanctions before the end of his term, which included an arms embargo and targeted financial restraints to individuals in the government and rebel groups. The new Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, has taken a softer approach by leaning on the African Union and the IGAD to negotiate the peace. However, individual countries have followed the call for a tougher stance by passing their own sanctions.

Understanding the Roots of the Conflict in South Sudan

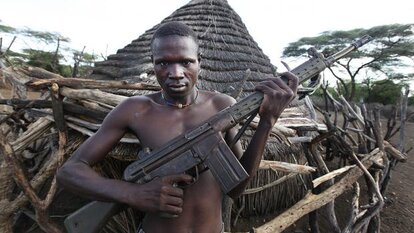

The conflict started in 2013, two years after South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on 9 July, 2011. It all started as a power struggle within the ruling party, the South Sudan Liberation Movement (SPLM). President Salva Kiir dismissed his entire cabinet and Vice President Riek Machar accusing them of plotting to overthrow him. Riek Machar denied trying to start a coup and fled to form and lead an armed faction, the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – In Opposition (SPLM-IO). Riek Machar turned to his Nuer ethnic group for support to wage war against President Kiir, whose primary support came from the Dinka ethnic group (who are also a majority in the national army). Conflict in South Sudan thereafter continued to thrive on conflicting interests of several ethnic groups. Both the ruling and opposition parties took to guns rather than turning to any democratic means to contest for power. The crisis in South Sudan intensified as fighting between the two rebel groups intensified. People fled to neighbouring countries and refugee camps set by international communities as a part of their peacekeeping intervention. Both sides committed abuses that qualify as war crimes, including looting, indiscriminate attacks on civilians and the destruction of civilian property, arbitrary arrests and detention, beatings and torture, enforced disappearances, rape including gang rape, and extrajudicial executions. Some abuses also constituted as crimes against humanity. The conflict has also created Africa’s largest refugee crisis since the 1994 civil war in Rwanda. Lack of a sense of accountability from both sides continued to fuel the violence, while progress on establishing the hybrid court as envisioned in the 2015 peace agreement was slow.

The Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the eight member trade block in Africa, has been playing a critical role in trying to mediate and negotiate for peace between the two sides. Several rounds of ceasefires fell through on account of disagreements over the terms settled or breach of the same from either or both sides. This continued until August 2015 when President Kiir signed a peace agreement previously signed by Riek Machar called the Compromise Peace Agreement (CPA) mediated by IGAD. With that, the situation looked as if Riek Machar was reinstated as Vice President. Machar returned to Juba with troops loyal to him. A Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission was established to monitor the implementation of the Agreement. Uganda voluntarily withdrew its troops from South Sudan in compliance with the peace agreement. At this point, President Kiir decided to increase the number of states from 10 to 28 in the pretext of ensuring smoother administration. He appointed officials who owed him allegiance as governors of the new states. The new borders gave President Kiir’s Dinka people the majority at strategic locations. Some observers felt that the government was superficially holding on to the peace deal to ensure the inflow of international monetary aids while actually backing campaigns to increase Dinka control over land and resources that were traditionally held by other groups. The President’s real intent did not go unnoticed by other ethnic groups. The outcome was the formation of several rebel factions that were dissatisfied with the government. For instance, the Shilluk people joined the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – In Opposition (SPLM-IO) at first but eventually formed the “Tiger Faction New Forces” rejecting the government, the SPLM-IO and the peace agreement and calling for restoration of the original 1956 borders of the Shilluk territory.

Another new faction calling itself South Sudan Federal Democratic Party, mostly made up of Lotuko people, came together to protest mistreatments by the Dinka government. In the years 2016 and 2017, it was this kind of rebel group infighting that renewed violence and conflict in the region. Riek Machar flipped back to armed struggle against President Salva Kiir, stopped compliance to the Peace Agreement and appealed that the terms of the agreement must be revised. The African Union and United Nations Force Intervention Brigade backed plans for deployment of troops from regional nations to protect civilians. President Kiir’s government initially opposed the idea calling it a violation of its sovereignty but soon had to give in under the threat of an arms embargo if the military deployment was stalled by the government. UN Mission in South Sudan failed to protect civilians in Juba. The fighting spread from Greater Upper Nile to the previously safe haven of Equatoria, which is the agricultural belt of the country. This aggravated the situation by increasing starvation to six million people. A large number of factions emerged in 2017 and 2018 to claim rights of small groups of people. Cracks have now emerged along clan lines among the ruling Dinka as well. Perceiving this, President Kiir has reduced the power of the Chief of Staff position and has fired one of its powerful nationalists, Malong Awon, who in April 2018 announced the launch of a rebel group named South Sudan United Front that is now claiming to push for federalism. South Sudan is currently acutely infested with factionalism and conflict of interests.

Understanding the Impact of the Conflict in South Sudan

Seven million people, nearly 60 percent of the population, require humanitarian assistance. A cessation of hostilities agreement signed on 21 December 2017 has not interrupted violent clashes between government and opposition forces in Central Equatoria and the Unity state. Unity state has also seen an increase in cattle raids due the resurgence of some armed groups. Meanwhile inter-communal tensions remain high in the Jonglei, Lakes and Warrap states.

The UN refugee agency UNHCR says there are 1.5 million South Sudanese refugees in neighbouring countries, excluding the more than 2 million displaced in UN Protection of Civilians sites.

The crisis reflects a steady deterioration since 2013 when the conflict began and the humanitarian crisis is expected to be worse in 2018 as conflicts persists. Farming is disrupted, humanitarian access in restricted, the economy is further destabilised and household coping capacity dwindling. The socio-economic and educational infrastructure has been destroyed, taking the family support system with it. The atmosphere of continued fighting has made it all but impossible for relief agencies to provide services. The innocent victims of the war are civilians who are forced to choose between disastrous alternatives: if they flee, they lose their homes, their livelihoods, and their communities; if they stay, they watch their homes being destroyed.

Women and children are suffering the most. Hunger and disease are widespread, and immunisation programmes have been curtailed. Very few school-age children are receiving an education, and children are subject to kidnapping and abuse from soldiers. There may be as many as 3 million people displaced, with 1.5 million living in settled areas and over 700,000 people in camps in the Khartoum area. Relief aid in the camps is unreliable, and the displaced women arrive with no assets or skills. They survive through domestic work, begging, petty trading, or beer-brewing and prostitution (the latter two are illegal). Children are left to fend for themselves all day or to find work in situations where they are exploited. In addition to depriving the children of their health, education, and economic stability, the war has resulted in cultural deprivation as ethnic groups lose their sense of identity. Psychological problems are the natural consequence of the situation, and aggressive behaviour is seen in the displaced children, while trauma and anxiety plague the children in the war zone. The government did little to end widespread abuses against civilians, or investigate and hold accountable individuals and commanders. Government investigations into violent episodes since the beginning of the conflict rarely led to credible prosecutions for human rights abuses.

International Community: On the Possibilities of South Sudan Elections in 2018

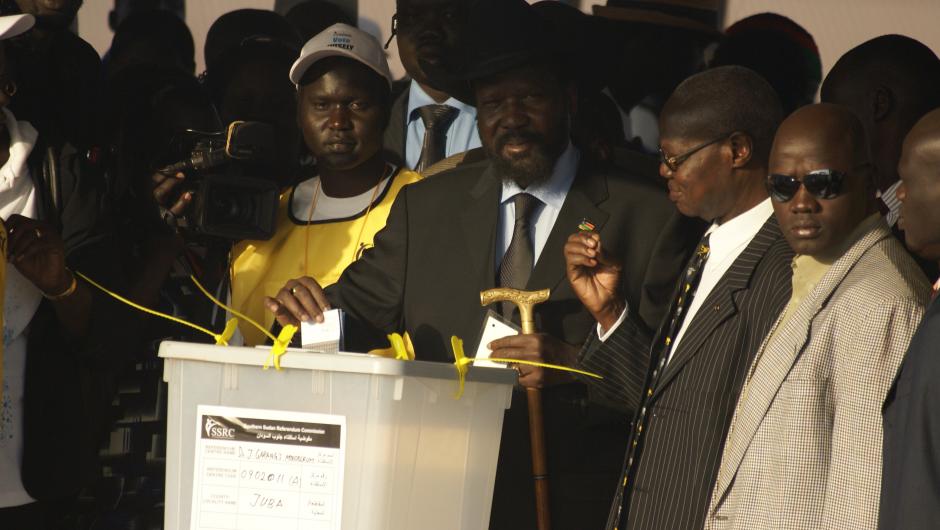

There are a lot of expectations for international actors to play an important role in ushering peace and security (specifically in mediation and peacekeeping) as well as extending humanitarian and monetary support in the war torn South Sudan. The most prominent external actor has been the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), which operates under the auspices of the African Union (AU). IGAD assumed the peacemaker role from the beginning of the conflict, establishing envoys to mediate talks. One of these talks resulted in the 2015 peace Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS), however, it did not hold in spite of IGAD deploying teams to monitor compliance. Individual countries within IGAD have also played a significant role in the unfolding crisis. For instance, the Solidarity Summit on Refugees co-hosted by Uganda and the UN on 22-23 June 2017 demonstrated the role that Uganda plays in hosting displaced people. Ethiopia and Kenya have played vital roles and displayed their commitment to peace building in the region by hosting refugees from South Sudan. Ethiopia hosted just under 500,000 refugees and Kenya about 100,000 refugees. Consequently, East Africa is the fastest growing refugee host region in the world, which shows the extent to which South Sudan’s neighbours have become involved in the conflict and affected by its by-products. South Sudan has not had democratic elections since it won its independence from Sudan in 2011 after more than two decades of civil war that ended with President Salva Kiir ascending to power through referendum vote, ushering in a transition period in the oil-rich yet impoverished country.

By and large the international community is of the opinion that the country must focus on the peace process rather than on conducting elections or extending presidential terms. The African Union is warning South Sudan that it is not stable to conduct free and fair elections due to the delayed implementation of key election provisions in the Agreement on Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCISS) to end more than three years of conflict. The United Nations opposes a plan by South Sudan's government to move to elections if warring parties are unable to reconcile differences at peace talks. South Africa based law expert Remember Miamingi is of the opinion that the elections are not peacemaking mechanisms, but could only be conducted when there is peace and security in South Sudan, noting that more than half of the population are still in Protection of Civilian sites and refugee camps. Experts interviewed by Xinhua (Media) in Juba said that the Transitional Unity Government (TGoNU) did not expedite the process of setting up the National Constitution Amendment Commission (NCAC), which is crucial for drafting and reviewing election laws that could affect the 2018 polls.

According to the ARCISS, some missing links that nearly take away chances of an election in South Sudan are that of the amendment of the National Elections Act in 2012, which was supposed to happen as per the ARCISS within six months of its signing and has not yet been done. Second, the National Election Commission which is to be reconstituted and appointed by the President and his first Vice President also has not been done.

The most critical caveat for conducting elections is peace and ceasefire in a country that allows its people to participate and vote. The prevailing insecurity that has caused mass displacements in several parts of the country would jeopardise the participation in elections.

Elections would also cost a lot of money for a country that is nearly bankrupt, executing an electoral process is definitely a challenge. Some feel that “Peace, security, safety and food are the immediate need of the South Sudanese. Elections are the immediate need for those struggling to purchase legitimacy.” On the other hand, there are also few like Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni that believe an election in South Sudan is the best way to achieve peace and stability.

The Women’s Block of South Sudan is a coalition of women led organisations formed to represent the voice of a large number of South Sudanese women, who are scattered in refugee camps or have fled to neighboring countries for refuge. It is calling for an end to conflict in South Sudan. It is appealing to the government and the opposition to end hostilities. The group is appealing to all native women of South Sudan to come back to their country and rebuild the nation through participation and involvement. The group is a signatory to the recently signed Cessation of Hostilities in South Sudan deal signed in Addis Ababa. The signing was organised by the regional East Africa group, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). Their appeal reinstates the faith in the fact that South Sudanese people still have the hope of coming out of war.

Bintou Keita, Assistant Secretary General for Peace Keeping Operations also talks about the high-level shuttle diplomacy taking place to try to reduce the gap between the parties and improve prospects for success at talks that have not materialised three times in the past. “With ministers, the international community and South Sudan's government engaging in the high-level diplomacy, I think we have a better chance to make progress on narrowing differences,” Keita said.