Survey

Europeans would like to see values-based foreign policy and ditch veto

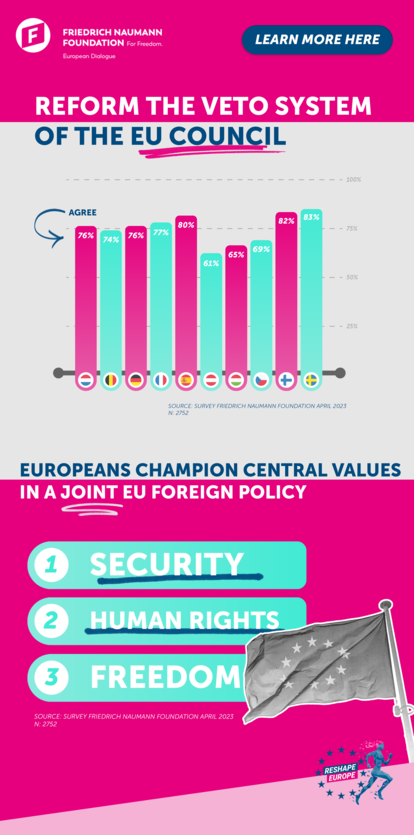

Europeans would like to see an EU foreign policy based on values. They want it focused on security, human rights and freedom. Also, most believe that the veto-system of the EU Council, which enables even single EU member states to halt or delay joint decision-making, stands in the way of a more unified foreign policy.

These findings are derived from a recent survey conducted among 2,752 EU citizens across ten member states. The Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF)'s European Dialogue Office in Brussels has commissioned this survey.

These figures go further than what we have seen in other surveys since the outbreak of the Ukraine war. The war has undoubtedly led to a refocusing of minds. What does the European Union stand for and what does it mean for the future of European citizens?

Second fiddle

For many years, European foreign affairs was the domain of diplomats and a couple of experts. The EU played second fiddle on the world stage behind some of its bigger member states, in particular those who are permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as Germany and, occasionally, Italy and Spain. Today, the European Union is perceived more and more as an international player in its own right. In trade negotiations, this has been the case for a long time. But the world has now become increasingly aware of the effect that EU decisions have on international economic developments, for example, as a result of its anti-trust regulations, which affect global companies, or of its environmental regulations which, in effect, are already setting new global standards because of the mere size of the European market.

This increased role of the EU on the world stage is perhaps more by accident than by design, although the 2011 establishment of the European External Action Service (EEAS), in effect the EU’s Foreign Office, led by a High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (in other words, an EU Foreign Minister) is beginning to make a real difference. The current High Representative is Josep Borrell, who previously was President of the European Parliament and Spanish Foreign Minister and is therefore able to speak with some authority.

The the world outside Europe is taking the EU more seriously. And, as the survey shows, European citizens have begun to take an interest.

The history of big and impactful EU interventions first started with some careful peace-keeping operations, for example in former Yugoslavia. Since 2002, which marked the end of the war in Yugoslavia, the EU has intervened militarily abroad thirty times in Europe, Asia and Africa. And in recent years, the EU has taken a global role where it addresses both climate change and sustainability. It also played a major leadership role during the Covid pandemic. Both topics were more or less forced upon the European decision-makers.

The real change, however, has come recently, with the Russian assault on Ukraine as well as the growing awareness of the role that China is carving out for itself on the world stage, and the interference of both China and Russia in democratic processes in our own countries. Leaning back is no longer an option. The results of our survey confirm this.

Joint foreign policy

In 2019, before the Ukraine war, climate change was the Europeans’ top priority. This priority, at the time, was followed by poverty, terrorism, and unemployment. Now, four years later, because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more than three-quarters of Europeans want a stronger joint European foreign policy. At the national level, this figure is lowest in France, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Austria, although still above 75%. In Belgium, Spain and Finland, on the other hand it goes even above 89%, 91% and 95%. There is similar support for stronger defence and security cooperation.

Indeed, security is the single most important priority of the EU’s foreign policy. It is closely followed by the defence of human rights and democracy. This has been the same result for all ten countries surveyed.

This shift is significant. After all, in the past, supporting the EU was often sold to reluctant European citizens as being in their natural self-interest. One would then have expected economic growth and trade to top the list. But these are now a distant third and seventh on the list of our respondents’ priorities. The debate about the systemic rivalry between Europe and China has also played its part. “Countering the influence of China” is fourth on the list of foreign policy priorities.

There is thus a clear need for a more effective and coherent joint foreign policy. A majority in all ten countries surveyed believes that the veto-system, whereby a single member state can block foreign policy decisions, stands in the way of that. In the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain, Finland and Sweden even more than 75% of respondents would like to ditch the veto. They thus support an initiative of a group of nine European Union countries who have joined forces to reform the voting rules that currently apply to the bloc's foreign and security policy decisions, which are governed by unanimity and often fall victim to the veto power of one single member state. The newly-formed "Group of Friends on Qualified Majority Voting" consists of Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Spain, and is open to other countries who wish to join.

Hungary, in particular, has been heavily criticised for generously using its individual power to block key agreements, such as an EU-wide ban on Russian oil imports, an €18-billion financial aid package for Kyiv and a deal to impose a 15% minimum corporate tax. The vetoes were eventually lifted, but only after the Orban-government‘s unilateral demands were met in full. Under such circumstances, the veto mechanism is obviously prone to be turned into a tool for political blackmailing. Another headline-making case occurred in September 2020, when Cyprus single-handedly blocked EU sanctions on Belarus because of an unrelated dispute with Turkey.

National identity

This shift in public opinion on the veto power is significant, too. Foreign affairs is justifiably seen as an important part of national identity. How countries present themselves on the world stage reflects on what they stand for, in other words on “who they are”. The national veto on European foreign affairs was a reflection of this desire to safeguard these national identities of all 27 member states. Now, however European citizens apparently also desire a joint European identity on the global stage, and this should be done in an effective manner without one single member state being able to stop the entire EU from moving forward.

It also shows something else, which is perhaps even more significant: namely that Europeans believe that there is such a thing as a nascent European identity, probably next to or on top of national and regional identities. From there, it is not a huge step to recognising that there actually is a European polity – a political sphere that goes beyond the national boundaries of the EU member states. The perceived wisdom was that no such political sphere existed or even could exist at European level and that citizens’ political involvement and identification was confined to the local and the national political space, in the same way that there are, or were, no Europe-wide media. There is still quite a way to go, but it is no longer as unthinkable as it was for many years.

Download the full survey below.