Georgia

Georgia is Europe!

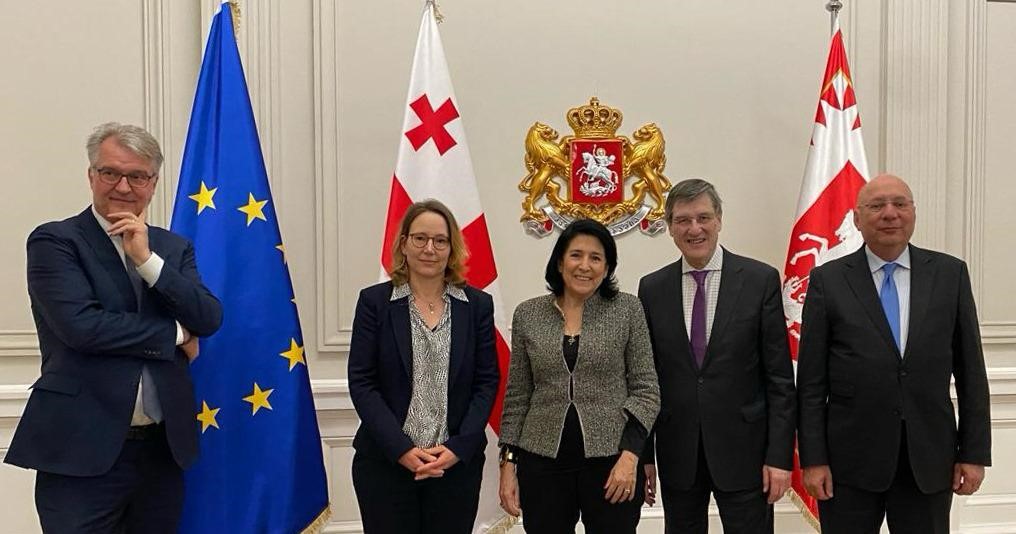

Die Georgische Präsidentin Salome Surabitschwili (Mitte) mit Martin Kothé, Kathrin Bannach, Prof. Dr. Karl-Heinz Paqué und Dr. René Klaff, alle von der Friedrich Naumann Stiftung für die Freiheit

© Pressestelle der Präsidentin von GeorgienThe author, Chairman of the board of directors of Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, spent 2 1/2 days at a regional strategy meeting of the foundation in Tbilisi. He and his team had extensive talks with Madame President Salome Zourabichvili and with leading liberal parliamentarians. He also addressed a meeting of start-up entrepreneurs. Here is his report from his visit to Georgia, his first one since 2016.

This is Europe! That´s the first impression you get upon arrival in the capital of Georgia. That is so despite the fact that you find yourself at the eastern edge of the old continent “behind” the Black Sea, on the southern slopes of the Caucasus, at the gateway to Asia, not far away from Iraq and Iran. The beautiful architecture in the main alleys spreads a flair of Paris, the Christian orthodox churches dominate the cityscape of the centre, the narrow streets of the old parts of Tbilisi convey a Mediterranean flavour. And not to forget the excellent local food and wine that is served in the bars and restaurants, all in the best European gourmet tradition.

The political mood of the population supports this first superficial impression. Polls persistently show that about 90 percent of the population proudly call themselves Europeans and aspire a membership of their country in both the European Union and in NATO; and they want to join as soon as possible, the quicker the better. The official promotion to EU candidate status in late 2023 was widely perceived as a great success. Of course, a good part of these warm feelings is the reaction to the Russian power and aggression that Georgia has experienced so often in its history, most visibly in the 2008 war, which led to the factual loss of control of 20 percent of the Georgian territory, the two provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. And, of course, Russia’s brutal attack on Ukraine further fuelled the pro-EU and pro-NATO flames. But it is quite obviously more than that, namely a deep emotion of belonging to Europe and the West that is rooted in history and survives in all circumstances.

Am 24. Februar 2024 demonstrieren Georgier in Tblisi in der Erinnerung an den Beginn des massiven russischen Angriffskriegs gegen die Ukraine zwei Jahre zuvor. Die Menschen schwenken Flaggen der Ukraine, Georgiens, der Europäischen Union und der USA.

© picture alliance / Anadolu | Davit KachkachishviliThe economics of the country confirms this picture. A remarkable digital start-up community has emerged, supplemented by the – possibly temporary – inflow of many Russian information technology experts in Georgian exile, who left their country due to the war that overshadows their business prospects and personnel life. As they drive up rents and prices, they are no more than accepted and not really welcome by the Georgian population at large (although they have pushed up the country’s GDP!). Whether they will leave again or stay is still open for many, but even if their Georgian exile ends soon, they are likely to leave for Europe or the US and not for Russia, thus adding, if anything, additional force to the western business trends.

Clearly, then, Georgia is firmly heading towards the West. However, on its way, there are still huge hurdles to overcome. The main one of these is what may be called the “immaturity” of the young Georgian democracy as virtually every Georgian intellectual acknowledges with an admirable sense of humour and irony. Politics is dominated by big parties with not much ideology, but with powerful oligarchs and plutocrats such as the super-rich Bidzina Ivanishvili from the governing party "Georgian Dream" (GD), which grew up as part of the global Social Democratic family, but since long leans towards right-wing populism. The second big party is Mikheil Saakashvili's United National Movement (UNM), which governed before GD, is almost equally hard to pin down on ideology - if anything, it is a bit more oriented towards the West. UNM is presently the major opposition group in the country.

In between GD and UNM, more genuinely liberal forces have a hard time to develop. In the parliamentary elections in 2016, the two liberal parties, the Republicans and the (Georgian) Free Democrats, missed the then prevailing 5 percent-clause although they both scored well above 4 percent so that, together, almost 10 recent of the population voted liberal. They did not recover from this blow so that, in the elections in 2020, when the 5 percent-clause did not apply, they became virtually invisible as a political force. In the upcoming elections, liberals will be back on the campaigning stage, but with a total of five (!) parties, which is way too many in such a small country. As the 5 percent-clause has been re-introduced, they are likely to split their potential of votes again. Obviously, they must join forces to make a difference. Presently, there are serious talks about a cooperation, but it is not yet clear what the outcome will be.

Whatever the outcome, liberal parties face other major challenges. The most serious one is the “state capture” of the ruling GD, which partly follows the right-wing populist pattern used by Viktor Orbán in Hungary. Large parts of the media are indirectly government-controlled and use all standard tools to discredit the political message of liberally minded political competitors. In this respect, a major topic are LGBT+ rights, which are scary for large parts of the conservatively minded electorate. Although they will clearly not be in the focus of liberal campaigning, which will feature much more down-to-earth topics like economic growth, new jobs and more employment, better wages and less price inflation, the GD-biased media again and again pick out LGBT+ rights as “the” major topic of liberal programmes.

In a similar spirit, the government manipulates the rules of the democratic game to adjust the political environment to their advantage. The playing around with the 5 percent clause in parliamentary elections – applied in 2016, removed in 2020, re-introduced in 2024 – is just one example among many. Another major one is the recent shift from a more presidential to a more parliamentary democracy. Formerly, the President was elected directly by the people; in the future (beginning 2024/5), he or she will be elected by a mostly parliamentary vote, which obviously deprives him or her of much power. Again, the governing GD stands behind this constitutional change, which is likely to reduce the trust in democratic institutions, not least because of the recent encouraging experience with the current Mme President Salome Zourabichvili.

Her career is remarkable. She grew up in Paris as the daughter of an exiled Georgian family, later joined the Georgian diplomatic service, became Minister of Foreign Affairs and was elected with the support of GD as President of Georgia in 2018 by a narrow margin of the popular vote. In the last years she became an outspoken advocate of the rule of law, fair democratic procedures and civil liberties – and against state capture. She also strongly supported the European and western aspirations of the country and did so much more consistently than the government. All this raised her popularity, which was rather low at the beginning – maybe a genuine indicator of evolving trust into a leading politician and authority. What followed was a Georgian-style attempt at impeachment – on the legal grounds that she violates her duties. The attempt failed miserably in parliament – and now enjoys even greater popularity and respect for her remaining time in office, which ends in December 2024.

Obviously, this is not how a mature democracy should work. In this sense, Georgia still has a long way to go. Maybe the emergence of a personality like Mme President Salome Zourabichvili could be an opportunity to speed up the process of maturation. At present, it is unlikely that she will continue with whatever political career in the future; at least this is what the rumours say. However, even without a powerful political position, she may remain as an authority supporting the country on its wrinkled path to become a genuinely liberal democracy that someday qualifies for EU-membership.